Testimony of Rohit T. Aggarwala Commissioner New York City Department of Environmental Protection before the New York City Council Committee on Environmental Protection

March 25, 2022

Good afternoon, Chair Gennaro and members of the Environmental Protection Committee. My name is Rohit Aggarwala. I am the Commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and the City’s Chief Climate Officer. I’m still quite new—I’m on the last weekday of my sixth week here—and I am excited to work with all of you as both DEP and the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice prepare the city to meet the environmental needs of the coming decades.

I am here today to discuss DEP’s Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2023, its Preliminary Capital Plan for Fiscal Years 2023-2026, and our performance on the Fiscal 2022 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report. I am joined today by DEP’s Chief Operating Officer Vinny Sapienza, Chief Financial Officer Joe Murin, and Acting Deputy Commissioner of Public Affairs and Communications Mikelle Adgate. I have been honored to take over as Commissioner from Vinny Sapienza, a lifelong dedicated DEP employee who was an excellent commissioner. I am very grateful—as we should all be—that he is staying on as Chief Operating Officer.

At the start, I would like to assure you that DEP is in strong shape. We have the best drinking water of any American city and our water rates are much lower than in most cities. New Yorkers experience far fewer water main breaks or service disruptions than residents of almost every other large city. Our harbor has seen a rebirth as a vibrant estuary, and our water supply is safe, secure, and clean. Further, while the City’s overall budget and headcount have grown dramatically over the last five years, DEP’s headcount has remained stable, and our operating expenses are up by only 1.1 percent annually over the last five years—in other words, DEP’s spending has increased at a rate below the rate of inflation.

Financial Structure & Customer Service

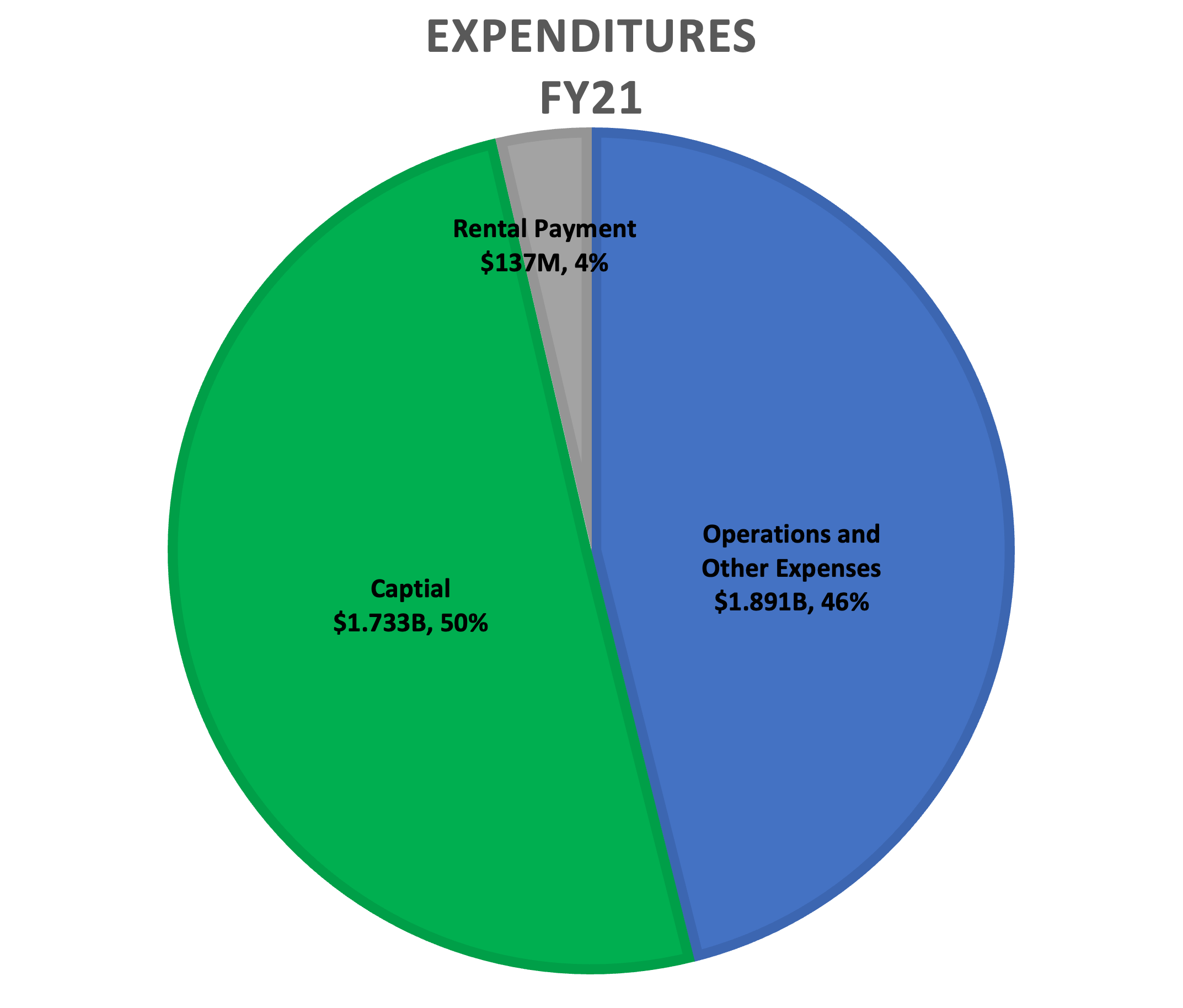

To begin, DEP is a hybrid agency. It is both a water utility and an environmental regulator. Roughly 2.2% of our expenses and 4% of our headcount relate to the environmental regulator function of the agency and are funded out of the City’s general tax levy. These functions include air and noise code enforcement, and asbestos inspections. The water utility function—the vast majority of our work—is funded directly out of water rates. In FY2021, the City’s water revenues were $3.665 billion. Of that, $1.733 billion went towards operations and other charges, $1.891 billion went towards capital (both directly funded and debt service), and $137 million went to the rental payment. [See Appendix 1: Expenditure Chart]

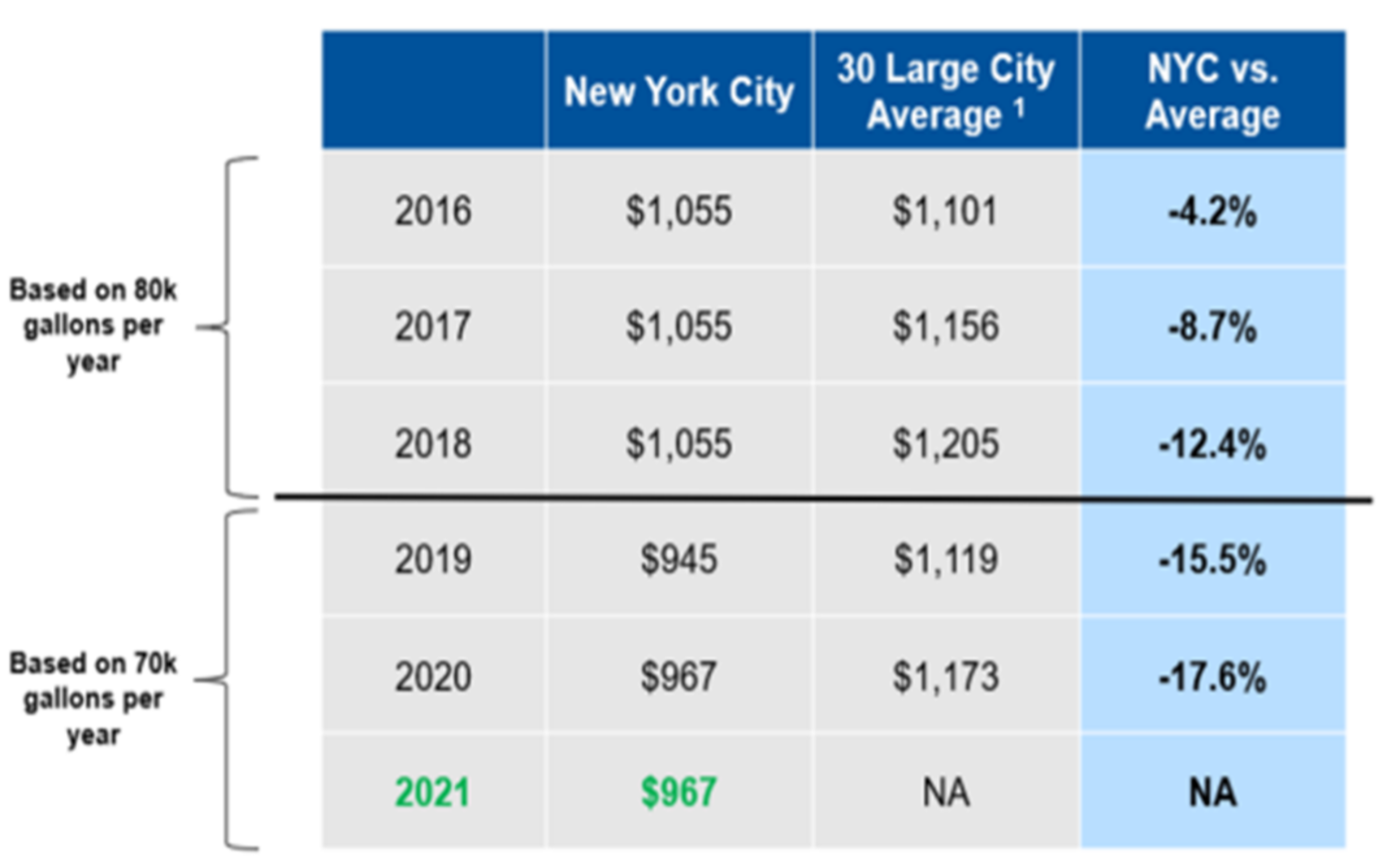

The Water Board’s public rate setting process will kick off later this spring, so I cannot speak to the future water rate now. The process will include public meetings, so you and your constituents will be prepared for any changes to the current water rate. New York’s water rates are much lower than in other cities [see Appendix 2: Water Rate Comparison]. Continuing to keep rates affordable is a key objective of our long-term planning, as is the need to maintain our financial health so as to preserve the high credit ratings that enable us to finance more than $30 billion in current outstanding capital debt.1

Each Fiscal Year, the City is entitled to request a rental payment from the Water Board. In FY2022, the City did not request a rental payment. In FY 2020 and FY 2021, the City made partial rental payment requests. The City has not indicated an intention to request a rental payment for fiscal years 2022 through 2026 as of this time.

DEP’s finances are shaped in part by our billing system, which is also our main point of interaction with our almost 1 million account owners. We are very proud of the fact that over the last year, DEP implemented a new, state-of-the-art billing system. Over the next year or two, we will have the opportunity to explore the kinds of benefits this billing system can offer, which including helping us understand customer behavior better, send out more targeted and customized notices, and perhaps even move towards billing outside of the standard 3-month cycle.

The combination of automatic water readers and our new billing system gives us great insight, but also creates information that is potentially highly sensitive. We are highly cognizant of the privacy implications of the data we hold and the need to comply with city, state, and federal privacy laws pertaining to utilities.

We know that some New Yorkers have difficult paying their water bills. To help, we offer a variety of options and programs, including:

- a Leak Forgiveness program;

- a Multi-Family Conservation Program;

- the Home Water Assistance Program, which provides over 50,000 lower-income homes with bill credits;

- New York State’s recent program to help people with outstanding water debts, which can offer low-income New Yorkers up to $5,000 to pay off overdue water bills; and

- individualized payment plans for any account holder who has outstanding water debt, which can stretch out payments and reduce or even forgive interest on overdue bills.

Our collections are of major concern to the agency’s fiscal health. As of today, we have more than one billion dollars in overdue payments, which is about 40% more than was overdue two years ago, prior to the pandemic. This week, we started mailing notices to customers with delinquent accounts letting them know about the multiple assistance programs we offer. Collecting ample revenues is what keeps the Water Authority’s credit rating high and borrowing costs low. If DEP is unable to collect owed revenue, the losses will lead to higher water rates for those who do pay their bills. In conjunction with our colleagues at the Department of Finance, we look forward to working with you to find the most equitable way to enforce payment obligations while protecting those who genuinely cannot pay.

Water Supply System

There is no question that the crown jewel of our water system—and probably of our entire municipal infrastructure—is our water supply system.2 Not only is it extensive, clean, and reliable, but it is also efficient—gravity-fed and largely unfiltered, our water supply system consumes very little energy compared to other cities’ systems. [see Appendix 3: Water System Map].

In general, I am happy to report that our water supply infrastructure is in good shape and highly robust. We have a significant ongoing capital investment program that is increasing the system’s reliability and redundancy, and we are undertaking the kind of major reinvestment that must happen every hundred years or so, such as our Ashokan Century program to renew one of our largest reservoirs, in the Catskills.

A few items I will bring to the committee’s attention respecting our water supply:

First, we are currently undertaking the scheduled mid-point review of our Filtration Avoidance Determination. That agreement, with the State Department of Health, runs through 2027. DEP submitted its recommended adjustments to the program in December. These were largely based on a review done at our request by the National Academies of Science, which indicated that our land acquisition program in the watershed had been highly successful, but in most cases has diminishing returns going forward. DEP did not propose to end the program, but we did propose to reduce the target rate at which we acquire property.

Second, I will point out that DEP is a major presence in many of our upstate communities, and our activities are often treated with suspicion. We at DEP have to work diligently to ensure that we deepen positive relationships with our upstate communities.

Finally, I would like to point out that climate change is already affecting our watershed, and it has significant potential long-term impacts we must plan for. In addition to the damage and deaths it caused in the five boroughs, Hurricane Ida disturbed organic materials in the watershed. Some organic material, like soil and leaves, remained suspended and reacted with the chemical used in our purification process. This reaction increased the levels of a series of regulated organic acids (HAA5) in the distribution system. When the increase was identified our system, operators had to make a series of adjustments to reduce HAA5 levels. I assure you that the water continues to be absolutely safe. This incident demonstrates the many kinds of impacts we face as a result of climate change. Similarly, while New York has been generally free from drought conditions for decades, climate change threatens the long-term reliability of our supply, both because of rainfall changes and because of the way sea level change is affecting the Delaware River—from whose watershed we draw roughly half our water.3

Water and Sewer Operations

Once our water enters the city, it is distributed around the five boroughs through 7,000 miles of water mains and then back through 7500 miles of sewer mains.4 Overall, our Water and Sewer Operations continue to perform well. In FY2021, we had only 6.4 breaks per year per 100 miles of water mains, compared to an industry-wide best practice of 15.5 When breaks happen, we restore water service in an average of less than five hours, largely because we have multiple offices sited throughout the city. The number of recurring confirmed sewer backup segments has steadily decreased each year, with a five-year average falling by 4% in 2021. To prevent backups, we clean over 600 miles of sewer each year and replace nearly 30 miles.6

Overall, roughly 41% of our capital budget is dedicated to BWSO. The preliminary budget provides continued funding for several major BWSO projects. Of note is the continued funding for City Water Tunnel 3 and the buildout of sewers in Southeast Queens, which is now a $2.5 billion project.

Stormwater

Perhaps top of mind for many New Yorkers when it comes to our sewers is their performance during major storms. As we know, climate change is increasing both the frequency and the intensity of storms, as Henri and Ida demonstrated so devastatingly last year.

New York City’s sewer system was generally well-designed for the kind of regular rainstorms we experienced over the last century. Our current standard for sewers today is 1.75 inches per hour, which, historically, was only very rarely exceeded. At its most intense, Ida was dumping more than 3.5 inches of water per hour on the city’s hardest-hit neighborhoods. Developing a comprehensive, long-term approach for how to protect New Yorkers in this new level of storm intensity is a top priority at DEP and at the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice. The New Normal report that the previous administration released in November 2021 is a good start, but is not the final word on what this administration will do on stormwater resilience.

A key highlight of our resilience efforts to date is clearly our Green Infrastructure (GI) Program, for which we collaborate with several other city agencies. To date, we have constructed more than 10,000 rain gardens and 14,000 acres of Bluebelts. About 90% of our GI program assets are in environmental justice neighborhoods, including 85% of our right-of-way assets. We are also working on new approaches, such as daylighting streams.

Our GI program to date has been designed to reduce pollution from combined sewer overflows (CSO). We are now looking at how the GI program can be expanded to complement other infrastructure and effectively manage stormwater during extreme rain events.

I should point out that DEP’s assets end at the property line. DEP has water and sewer infrastructure under every street in the city, but property owners are responsible for maintaining all of the plumbing on their property. This includes the water and sanitary sewer service lines that extend from the property to the city’s water and sewer mains in the street. It is no different from a driveway—the street is owned and maintained by the city, but a driveway on private property is private.

There are many steps that property owners can take to protect their homes and businesses during storms. We offer a Homeowner’s Guide to Rain Event Preparedness on our website. For some buildings, installing a backwater valve may be helpful to protect a basement. The Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice is currently conducting a study to determine where backwater valves are appropriate.

Lead

The issue of city versus private infrastructure is a challenge to the goal of replacing lead service lines. The New York City water supply system is virtually lead free when it delivered, but water can absorb lead from solder, fixtures, and pipes found in the private plumbing of some buildings and homes. DEP does not have lead water mains, but we estimate that there are more than 130,000 New York City buildings that have private lead service lines. We work to reduce the risks of lead by carefully adjusting pH levels of the water to prevent corrosion and prevent lead from lead pipes from leaching into drinking water. We also provide free lead test kits to any resident who requests one. In 2021, DEP provided more than 7,000 free lead testing kits to residents across the city.

Traditionally, DEP has only worked to eliminate lead from City-owned pipes, but we recently launched a pilot program with state funds to help low-income homeowners replace these lines. We have replaced 280 lines so far and expect to replace more than 300 more with the existing grant funding. We are hopeful that federal funding may be available to expand this program significantly.

Wastewater Treatment

Protecting the harbor is the main task of the Bureau of Water Treatment (BWT) and its 14 Wastewater Resource Recovery Facilities (WRRFs). Each day, DEP treats 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater to meet the standards of the Clean Water Act. Since 2002, we have invested more than $14.5B to upgrade our treatment facilities. Thanks to advancements in our processes, New York harbor is healthier than it has been since the Civil War.

Through this work, we have reduced CSOs from 100 billion gallons per year 40 years ago to 18 billion today, an 80% reduction. Our work here is governed by the CSO Consent Order and our Long-Term Control Plans (LTCP), which were developed with the State DEC. We have already committed more than $6 billion in projects towards the LTCPs. The challenge we face now is that each additional gallon of CSO we prevent costs more and more, as the easiest solutions have all been done. This is a key reason that green infrastructure is such an important part of our overall strategy.

CSOs are not the only reason we need to invest in our recovery facilities. First, they have the potential to be a core part of the city’s overall sustainability effort, because the digesters that convert human waste to energy and material can also convert food waste to energy and material, as we currently do at Newtown Creek. Several projects to expand that capacity are in the budget.

Second, many of them are falling well short of a state of good repair. A meaningful portion of our capital budget is dedicated to this kind of work, and I expect it will grow in future budgets. The price of not maintaining these facilities is an increased risk of a catastrophic failure that will be expensive both financially and to the environment.

Finally, our recovery facilities are also on the front lines of climate change, as rising sea levels threaten our outfalls and will require redesigns over time. Preparing for our future reality does offer opportunities, such as the opportunity we have to explore the consolidation of four recovery facilities onto a site at Rikers Island. That study, required by Local Law 31, will kick off next month.

Security and Reliability

As you have seen, much of our attention, especially in our capital budget, is focused on preserving and enhancing our system’s reliability. We know that failures are always disruptive and are potentially catastrophic. In addition to climate change, we are also focused on protecting our system from malicious attacks. Cybersecurity especially is a top priority for DEP. As President Biden recently highlighted, utilities continue to be prime targets for cyber-attacks, and so DEP has developed a robust cybersecurity program. We work closely with federal, state, and local authorities, including NYPD Counterterrorism, the FBI, and US Homeland Security. As recently as this past Tuesday, DEP participated in a utility security call with the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). We have implemented several backup and contingency systems to ensure that the city’s water supply is well protected, and are engaged in regular exercises to ensure that we know what to do in case of a successful attack.

Environmental Regulation

As you can see, DEP’s role as a water utility is a large and critical task that is the bulk of the agency’s attention and budget. But we also have the crucial role of protecting the health and quality of life for residents by overseeing compliance with the Air, Noise, and Asbestos Codes. I will highlight two items here.

New York City is one of the few cities in the country with citizen participation in its idling control program. This program started in the 1970s but really took off in 2019 through a change allowing citizens to participate in enforcement. The program went from a handful of complaints submitted per year to over 10,000 summonses issued by DEP on behalf of the citizen complainants in 2019. DEP has been undergoing a rulemaking process to strengthen idling enforcement.

DEP also enforces sections of the Noise Code, including the section limiting the noise of vehicles. This is traditionally enforced by personnel standing beside streets taking noise measurements. We are currently piloting a meter-and-camera-based system to automate this enforcement. We currently have one meter-and-camera location for this pilot project, and will assess its accuracy and effectiveness before deciding whether to expand it.

Looking Forward

Several months ago, the federal government passed a massive infrastructure bill that includes funding for many water and sewer infrastructure projects. Most of the funding is allocated for grant programs and we are waiting for the grant requirements to be issued. We are optimistic, however, that we may be able to secure federal funding for a range of projects, including lead service line replacements, green infrastructure, and water supply work with our upstate partners.

Overall, I would like to conclude by saying that, in my first six weeks, I have focused on understanding the full extent of this important agency and its work. I have a long track record as an environmentalist, so I am very excited to be at an agency where the environment is, truly, our middle name. Over the coming months, I will be looking to expand DEP’s ambitions in air quality and noise regulation; reshape our role in the watershed; and place DEP squarely at the front lines of the fight to protect our city against climate change—and to forestall it. I will also be focused on ensuring that we operate effectively and successfully as an organization, considering the needs of our dedicated staff as well as the exploring the potential to do things better. I will also be very concerned with ensuring the security of our system, and its financial health and customer service. Inevitably, many of these plans are only just beginning, and I look forward to working with you on this committee as we develop new thinking.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My colleagues and I are happy to answer any questions that you have.

Appendices:

APPENDIX 1: Expenditure Chart

APPENDIX 2: Water Rate Comparison

APPENDIX 3: New York City’s Water Supply System

Footnotes:

-

Three entities are involved in our financial structure: DEP, the New York City Water Board (Board), and the New York City Municipal Water Finance Authority (Authority). DEP owns and operates utility system assets as a Mayoral agency. DEP’s Bureau of Customer Service handles the collection of water fees from city residents. The Water Board sets rates, collects payments, and is the leaseholder for City-owned utility assets. The Authority issues and manages debt. The Board and the WFA are State public entities. This system was established by state legislation in 1984. Per that legislation, the City has the right to collect an amount determined by formula as a rental payment for the pre-1984 city assets operated by DEP.

As part of its debt management responsibility, the Authority issues bonds. Last month, the bonds once again received a ‘AA+’ rating. This excellent credit rating allows the Authority to borrow money at lower rates of interest than less creditworthy borrowers. Interest payments are a system expense, so having a low interest rate means that water rates do not have to be raised to cover the additional expense of higher interest.

-

The watershed includes 19 reservoirs and three controlled lakes, which hold a total capacity of 570 billion gallons of water. The 1.2 million acres of watersheds traverse portions of eight counties, 60 towns, and 12 villages.

-

Roughly 50% of our supply comes from the Delaware System. The Delaware System is governed by a series of regulations, including a 1954 Supreme Court Decree that allocates how much water New York City can take from the Delaware River Basin. Rising sea levels and glacial rebounding are exacerbating the effects of salinity intrusion in the lower Delaware River. Currently, NYC is required to make releases based on the position of the salt front in the lower Delaware River during times of drought emergency. In the event that the Delaware River Basin experiences a significant drought, NYC may not have enough water in its Delaware Basin reservoirs to meet both demand and its release requirements in the Delaware River.

-

New York City has two types of sewer systems. In most of the city, the same sewer lines carry both sanitary waste and stormwater. This is known as a Combined Sewer system. In roughly 35-40% percent of the city, we have the Municipal Separated Sewer System, commonly referred to as MS4. In these areas, which are concentrated primarily in younger neighborhoods in Staten Island and Queens, sanitary sewage is handled by a dedicated sewer network that brings wastewater to be treated, while stormwater runoff is handled in a separate network that goes directly into waterways. Anything that enters the sewer through a catch basin in a MS4 area is released untreated to a local water way, so it is important to remind everyone that dumping into the sewer system is illegal and that every effort should be made to minimize litter in the streets. These are easy ways that all New Yorkers can help protect our harbor waters.

-

DEP’s remarkably low rate is due to BWSO’s robust maintenance program and advanced monitoring and management techniques. For example, BWSO monitors pressure throughout the system on an ongoing basis and can reduce water flow into specific sections that are at high pressure, thus reducing the likelihood of breaks. BWSO proactively replaces nearly 50 miles of water supply lines every year, about a mile per week.

-

Most of the cleaning is proactively done before a problem can arise. Maintenance used to be done on a fixed scheduled, but BWSO is instituting an innovative new approach to predictive maintenance that considers the size and age of the sewers, the local population density, and other factors (such as presence of restaurants) to inspect more frequently those sewers more likely to have problems.