Testimony of Rohit T. Aggarwala Commissioner New York City Department of Environmental Protection before the New York City Council Committee on Environmental Protection, Resiliency, and Waterfronts

April 26, 2024

Good morning, Chair Gennaro and members of the Committees on Environmental Protection, Resiliency, and Waterfronts. I am Rohit T. Aggarwala, Commissioner of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). I am joined today by Chief Operating Officer Kathryn Mallon, Deputy Commissioner of Water and Sewer Operations Tasos Georgelis, and Deputy Commissioner of Sustainability Angela Licata. Thank you for convening this hearing on this critical topic of stormwater resilience.

Download the full testimony and appendices

NYC’s coastal resilience path offers lessons for stormwater resilience

I do not have to tell you that climate change is real, and it is here. In 2020, the US National Climate Assessment reclassified New York City from the coastal temperate climate zone to the humid subtropical climate zone—a recognition that we now live in a place that our infrastructure was not designed for.

We face several types of flooding impacts and risks as a result. Rising sea levels are creating more frequent tidal flooding, which we have seen particularly, but not exclusively, in the communities around Jamaica Bay. Rising sea levels are also causing groundwater levels to rise, which is exacerbated during heavy storms and periods of long-term rainfall. Of course, this means an increasing risk of coastal inundation. I note that multiple forecasters have indicated that this hurricane season is expected to be more severe than average. [See Appendix 1: Flooding Types]

Today’s hearing is primarily about stormwater management, but before I turn to that I would like to say a few words about coastal defenses, given the forecasts. In the 12 years since Hurricane Sandy, New York City has pursued two, complementary kinds of coastal flooding strategies. One is about preventing storm surges from causing flooding; this is what coastal defenses are. The reality is that these major projects—such as East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR), Red Hook Coastal Resiliency (RHCR), and the South Shore of Staten Island seawall—are massive, complex projects that take years to design and years to build. We are making significant progress, and in fact we expect the first gates of ESCR to be turned over by the contractor later this year. Within two to three years, several of these projects will be complete, and many neighborhoods of New York City will be protected against storm surges. As of now, more than a dozen projects are underway, but none is complete and fully functional. The reality is that this year, if a storm surge hits New York City, there will be flooding. [See Appendix 2: Storm Surge]

The good news is that we have also invested huge amounts of money in resilience—which is not about preventing flooding but ensuring that we can withstand and bounce back from it. As we know, 44 New Yorkers lost their lives in Hurricane Sandy, and thousands had property destroyed, but among the storm’s major impacts was the long-term disruption it caused. Because so many buildings had their electrical equipment in the basements, many buildings were without power for weeks, and some—especially at NYCHA—were without elevators for months. We learned from this and now, happily, our building-level resilience efforts are well advanced. Our power plants and wastewater treatment facilities are better protected. Many buildings—including at many NYCHA facilities—have relocated or hardened their critical equipment. While a flood today would still cause damage, in most cases it would be the kind of damage that disrupts lives for hours, or a day or two, rather than months.

Overall, New York City will have invested more than $18 billion in coastal preparedness in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, mostly from Federal funds. Roughly speaking, somewhere between a quarter and a third of that is for building- or site-specific resilience, and the remainder is for large-scale coastal infrastructure. Even with this, the work is far from complete, and the US Army Corps HATS study will cost upwards of $50 billion. And we do not have a dedicated source of funding, either Federal or local, for coastal resilience.

I say this in part because of what we may face this summer, but also because the reality is that our stormwater resilience efforts really started in earnest only two and a half years ago, after Hurricane Ida, whereas our coastal work began twelve and a half years ago, after Sandy. As with coastal resilience, it will take well over a decade for us to see measurable progress in stormwater resilience infrastructure, and it will cost billions and billions of dollars. As with coastal resilience, building-level resilience will be much faster to achieve than infrastructure-level prevention, and the reality is that we will need both. One key difference is that we expect to pay for most stormwater resilience projects with local funding sources. That is of course both good news and bad news. As New Yorkers, we will be less dependent on state or federal decisions to shape whether we achieve stormwater resilience, but the bad news is that the more resilience we want, the higher our bills will have to rise.

Climate change is causing stormwater flooding by exceeding the design standards of the sewer system

How does climate change cause flooding? The heating caused by climate change adds extra moisture to the atmosphere, intensifying storms and making them harder to manage. These massive storms now bring short, extremely intense bouts of rain, which are called cloudburst events. The deluge from cloudburst events can overwhelm stormwater management systems.

For the past century, the New York City stormwater system generally performed sufficiently, capturing rainwater and carrying it to treatment facilities or open waterways. Storm sewer capacity varies around the city, but, at most, it is meant to manage 1.75 inches of rain per hour. Until recently, rain was expected to exceed this intensity only once every five years. In other words, there was a 20% chance that a storm would exceed this intensity in a given year.

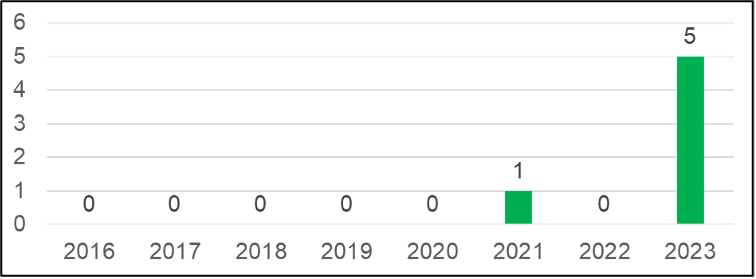

But now, we are in a subtropical environment, so we see these storms more frequently. Last year was especially wet. New York City experienced rain every three days in 2023, and experienced five storms that exceeded 1.75 inches per hour, as measured at our wastewater resource recovery facilities. Instead of one “five-year storm” every five years, we had five “five-year storms” in one year.

Number of days with > 1.75″ per hour of rain

It is possible that 2023 was an outlier. It may be that the next few years will be somewhat drier, but increasing overall rainfall is consistent with all climate models for the northeastern United States, The recent New York City Climate Change Vulnerability, Impacts, and Adaptation Study (a collaboration between the city and local scientists) concludes that the “five-year storm” toward the latter half of the century (2050-2099) is expected to be between 2.1 inches and 2.6 inches per hour. We are likely to face more extreme swings, so that we should expect to see more wet years punctuated by drought years. This is exactly what has happened over the last few years. It is easy to forget that, in between the record-breaking storm years of 2021 and 2023, 2022 was a drought year, with very little rain until the late autumn.

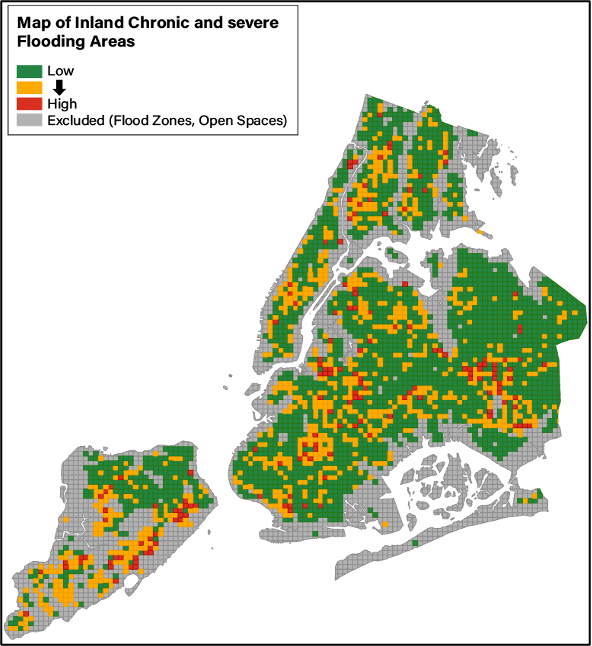

It is important to note that flooding is not uniform. It is perhaps obvious that areas at the tops of hills do better in storms than areas at the bottom of hills because water flows down and gathers in natural valleys. Many of our most flood-prone locations are the sites of former waterways or wetlands that were filled in for real estate development. Water doesn’t care that a stream has been filled in; it will continue to flow to that spot, as it has for millennia. Some parts of the city, notably in Queens, parts of Brooklyn, and the Bronx, are additionally challenging because their sewers were built to lower capacity standards back when sewers were handled by the borough presidents and were not uniform across the city.

To protect themselves, people must be able to understand how vulnerable their property is. To provide that understanding, DEP and MOCEJ have been working for some time to develop flood maps of the city. In 2021, we released stormwater flooding maps for future climate change scenarios. In 2022, as part of Rainfall Ready, the Adams Administration’s first step towards stormwater resilience, we released maps of flooding with current sea levels and in somewhat extreme storms (roughly 2.1 inches per hour, which, as mentioned above, is called a “ten-year storm” now but may be just a “five-year” event in the future as the climate changes).

Noting the request in Intro 815, I’m pleased to note that we are finalizing a new flood map showing those locations with flooding expected at the five-year storm level, which is about 1.75 inches per hour. This will soon be available on DEP’s website, along with the existing 100-year and 10-year maps.

It’s worth noting that these are just models, and data analysts have a saying that “all models are wrong” because they are at best approximations and estimates. One way we check our maps is to talk to you and your colleagues, as well as residents, when we do walking tours about how the map compares to lived experience. We’ve had good feedback, but it remains important not to mistake models for infallible fact. We’ve had several unprecedented storms and can only expect to have more. Also, of course, in a city as big as New York rainfall varies dramatically across the city. For example, on September 29, 2023, when north Brooklyn received 2.6 inches in the most intense hour of the storm—the second-most intense rainfall ever recorded in New York City—other parts of the city received less than 1 inch per hour. When I say that the city experienced five “five-year storms” in 2023, it doesn’t mean that everywhere on the flood map flooded five times.

One thing is clear in looking at these flood maps: flood risk is a citywide problem. Manhattan, due to its elevations, its bedrock, and the sewer policies of Manhattan borough presidents past, tends to do well, but even Manhattan has flood-prone locations especially in upper Manhattan where there were once streams and wetlands. I know that for each of you, your neighborhood’s flood-prone locations seem like the worst anywhere, but we need to recognize that this is a citywide problem and think about citywide solutions.

We have been working to improve the performance of the current stormwater management system

As I said, the fundamental challenge is that we have a stormwater management system that was designed for one climate and is now facing another. Our first step, and clearly the most cost-effective step, is maximizing the performance of our current system, and we have been doing that.

You all know that sewers are the first line of defense against flooding, and catch basins are the way that stormwater enters our sewers. Further, I know you all know that catch basins can be blocked in two ways. They can get filled up with debris, in which case DEP has to come clean them by removing the grate on top and scooping out that debris; or they can get matted over, in which case someone—which could be anyone—needs simply use a broom or rake to clear away the leaves and litter that are blocking the drain.

We are tackling both types of blockages. I am very proud of the data-driven catch basin inspection program that DEP implemented, thanks to Deputy Commissioner Tasos Georgelis, that optimizes the cleaning of our more than 150,000 catch basins Informed by past cleaning data, we target more frequent inspections in areas that are most likely to need cleaning.

We’ve also created a new fleet maintenance team to augment the work Sanitation and Parks do to maintain our vehicles. Given their design and the stresses they experience, catch basin cleaning trucks are inherently prone to breakdowns. Just last year, we hired our own small team of mechanics, and we are now better able to accelerate repairs to get our catch basin cleaning trucks back into service.

Our new inspection schedule and our new maintenance team have allowed us to increase catch basin cleanings by 22% through the first four months of FY2024 while overseeing a 45% decrease in the resolution time to clear a clogged catch basin. Today, I’m pleased to say, we clean clogged catch basins within three days of identifying that cleaning is necessary—whether they are identified by a 311 call or our proactive inspections.

To prevent matting over from completely blocking water from entering a catch basin, we have begun installing a new catch basin design that includes a second grate on the sidewalk. This additional, elevated grate allows the basin to function even if leaves cover the main grate during a storm. This additional grate can help prevent water from reaching private properties and causing damage in certain locations. While steps like this can reduce the instances of flooding, they cannot increase the overall capacity of the system. We have installed 50 slotted manhole covers through this pilot and have a target to install 100 this year.

We have also been doing more to clean out sewers than before. Over time, small debris and grease can build up on the inside of sewers, which reduces their capacity. In fiscal year 2023, we cleaned 692 miles of sewers—essentially 10% of our sewer network—employing vactor trucks and other cleaning methods to clear out accumulated debris. Cleaning alone won’t solve the capacity problem, but it can add a bit of capacity—and every little bit helps in a major rainstorm.

As I’ve discussed before, though sewers are the primary tool for managing stormwater, we rely on a suite of tools based on communities’ needs. While we are doing this improved sewer work, we are also continuing to implement our green infrastructure program. As I mentioned last month, in 2023 we added nearly one thousand new green infrastructure assets to our system, raising the total to 13,000. We are also making progress on cloudburst infrastructure which designs public spaces to retain water during major storm events. I’m pleased that our first cloudburst project, at the South Jamaica Houses of NYCHA, will break ground this summer. We have another four that are in design and that will enter construction over the next two years. We’ve had great success with obtaining and seeking federal money for these. We have been selected and are awaiting award of $123 million for cloudburst projects already and are applying for more funding for additional neighborhoods, including East Elmhurst and Central Harlem. [See Appendix 3: Stormwater Management Toolbox]

Finally, I should also mention that our Unified Stormwater Rule, adopted in early 2022 thanks to the leadership of Deputy Commissioner Angela Licata and her team, is having tremendous impact. The rule requires developers of sites greater than 20,000 square feet or those that add 5,000 square feet or more of new impervious surfaces to install on-site stormwater management practices when building a new development or significantly renovating an existing site. Since it took effect 25 months ago, DEP has approved permits for 500 properties that have implemented projects to capture nearly 40 million gallons of stormwater per year. Because of this rule, new development around the City means increased stormwater management. We also encourage green infrastructure on private property, including by offering a green roof grant program as well as Resilient NYC Partners, a program that provides technical and financial assistance to advance green infrastructure on large properties such as Greenwood Cemetery.

I will acknowledge that the Unified Stormwater Rule has caused complaints among developers—and fellow City agencies—about the documentation required and how long it takes DEP to evaluate applications. Figuring out how to streamline the rule—without reducing its impact—is a task that Deputy Commissioner Licata and I have prioritized for this year.

We have been working on longer-term stormwater resilience

As you know, and as we committed in PlaNYC, DEP has been working on a stormwater resilience strategy for the city.

Our first step was to ensure that our two stormwater planning organizations—the Bureau of Water and Sewer Operations’ Capital Program Management Group, led by Wendy Sperduto, and the Bureau of Environmental Planning and Analysis’s Capital Planning Group, led by Melissa Enoch, were staffed as fully as we could accommodate and were working together. Because green infrastructure in the past had been considered only as part of the City’s long term-control plan for reducing combined sewer overflows, DEP had not traditionally considered a mix of green and grey infrastructure to address a given flooding issue. Now, with great collaboration—which I would point out is led by great female engineers and planners—and working together, we are tackling this challenge in the right way.

Our second step was to assess how many locations are likely to require significant work to meet a basic level of future stormwater resilience. Over the past year, we completed a study to identify the areas in NYC most in need of stormwater flooding relief. This study looked at our flood maps, and incorporated community complaint records and sewer system capacity. We identified more than 80 discrete areas that experience the most chronic and severe flooding during a storm that produces 2.1” of rain in an hour. These areas represent 20% of the area in the city subject to street flooding during such a storm.

We have begun to build the tools we need to plan for resilience

Our third step was to build tools that would make our planning work easier and more effective. Previously, New York City had not invested in a digital model of our entire sewer system. This meant that we could not fully model flooding scenarios. Deputy Commissioner Georgelis, Director Sperduto, and I all prioritized this work, and under Wendy’s leadership this digital model was completed earlier this year, enabling us to identify efficient and cost-effective solutions to capacity limits in a way we have not been able to before.

The investment in this model is already paying off. We are now able more easily to identify where interventions are needed to reduce specific areas of flooding. Identifying these intervention opportunities is more complicated than one might think. Sometimes a corner floods because of an issue at that corner. That's easy to identify. Sometimes a corner floods because of an issue upstream or downstream of the corner, in a location that we hadn’t looked at before, because it does not have any flooding. That’s where this modeling system can help us identify the problem.

We are also using this tool to identify areas where we can use existing capacity more efficiently, by identifying ways to redirect flow and create new pathways to spread the volume. These innovations would use existing infrastructure to significantly increase sewer capacity and possibly avoid our needing to upsize miles of trunk sewers. We are early in this process, but I look forward to speaking to you all about its progress.

Before I move on, I want to stress this: the kind of dramatic planning we will need to do to re-engineer our system for a new climate will require not just a bunch of projects but will require us to invest in, and maintain, new tools that help us be much smarter about the work we need to do. As you ask us questions and seek to hold us accountable, I hope you think not only about the new things we build, but also about how we are managing and maintaining the tools we need to do the job, whether those are catch basin cleaning trucks or digital models for engineering.

We have used this model, and our new integrated planning approach, on a few sample locations

Our next step was to apply our model, and our new integrated planning approach, to a set of site-specific case studies around the city. The goal was to do some deep engineering assessments to see in depth what the needs were in each location, what the potential mix of solutions might be, and what an intervention might cost. We looked at four locations in depth: Dyker Heights, Kissena Park, Knickerbocker Avenue, and the Jewel Streets area.

I won’t bore you with the details of each assessment, but a few lessons emerged:

- Where there is excess capacity in sewer mains, the most effective solution will be ensuring the sewers in neighborhoods are large enough to convey the local flow to these larger trunk mains to take advantage of this capacity. This was the key lesson of the Dyker Heights case study, where we plan to upsize the network of local sewer pipes that lead to significant downstream capacity.

- Green and grey infrastructure can be complementary. In the Jewel Streets neighborhood, which sits at the lowest elevation in the area, we are exploring the combination of a bluebelt to capture and store stormwater alongside a larger pump station and trunk main capacity to effectively drain the water. Here, the combination of grey and nature-based solutions allow each to provide part of the solution.

- Green infrastructure can be effective, faster, and cheaper in some situations, but it can be complex to implement and maintain. In Kissena Park, one attractive alternative could replace some of the recreation space in the park with a bluebelt. Jointly with the Parks Department, we will need to see whether this is a change that residents would support. Further, green infrastructure tends to be more maintenance-intensive than grey infrastructure; we will need to ensure that responsibilities are clear and that maintenance funding is available, or else green infrastructure investments will fail for lack of maintenance.

- In some situations, expanding grey infrastructure, like trunk sewers, can be the most efficient solution to drain large volumes of stormwater from flood-prone locations. Bushwick has an extensive array of rain gardens and other green infrastructure assets that were built to improve water quality of stormwater runoff, However, he Knickerbocker area still faces regular flooding during significant rainfall events. The best solution in this area is to dramatically increase the size of the sewer that runs down Knickerbocker Avenue.

Stormwater resilience will need to be a citywide effort, not a service DEP provides

The task of designing and delivering major sewer and related infrastructure projects in the 80 or so locations we identified will take at least 30 years at our current funding levels of roughly $1 billion per year for stormwater-related infrastructure. And this is just to achieve a basic level of resilience, not at all to protect every New Yorker against all storms. Achieving protection from the kind of storm we experienced last September could cost upwards of $250 billion—a cost New Yorkers would need to bear in the absence of state or federal funding sources—and may not even be physically possible in some areas given limited space for larger sewers beneath our streets.

This work also leads to three other conclusions that I hope this committee takes into consideration.

The first is that, as a city, we will have to make decisions about the trade-off between more flood protection and greater costs for New Yorkers. We will certainly do everything we can to maximize federal and state dollars—and I thank the committee for Resolution 144 to help us get our fair share of funding from the state—but the reality is that the vast majority of our stormwater resilience efforts will be paid for by New Yorkers. However much we want to be protected, our costs will rise accordingly.

The second is that building-level protection is both faster and more cost-effective than neighborhood-wide infrastructure. The work New York City has done to make individual buildings more resilient to coastal inundation has moved much faster than our work to prevent coastal inundation. In the same way, building-level stormwater resilience will be faster and usually cheaper. Pursuant to Local Law 1 of 2023, we have been developing a plan for a backwater valve program ande are on track to meet the requirements of this local law. We don’t see this effort as a replacement for infrastructure, but as a complement. The City’s infrastructure should expand to deal with our new weather patterns, but homeowners and building owners will also have to do more to protect their own property and create resilience. This may also mean using basements differently, just as was required in the coastal flood plain after Sandy, and as Intro 815 implies. It might mean doing more onsite to manage stormwater, like disconnecting roof runoff from sewer lines to removing impermeable surfaces or installing drywells. How we accomplish this is still to be determined, but it is likely that the City will need to do more to provide technical assistance to property owners to make their properties more resilient.

The final conclusion I ask you to think about is that this is not just a technocratic decision. DEP alone cannot deliver a stormwater resilience plan for the city. We will need a much broader conversation about how much we are willing to pay, how much flooding we are willing to accept, and what kinds of responsibilities we are willing to impose on homeowners. DEP is the right agency to offer alternatives, but these are fundamentally political questions.

What DEP Needs from The Council

I very much appreciate the impulses behind several bills being heard today, and I believe there is a path forward to crafting legislation based on both Intros 814 and 815 that we would support. However, these are complex issues and I hope that the Council does not seek to legislate hastily.

We support the idea behind Intro 814, which is to codify our ongoing stormwater resilience planning into law. However, many of the specifics in this bill are problematic, and others miss the main need and instead mandate reports and disclosures that will distract our staff without creating real value for the public. Given the update I have provided today I hope this committee appreciates that we are taking stormwater resilience planning very seriously and that you will work with us to codify an approach that gets this right. This will require setting reasonable definitions of what the Council will require DEP to assess, reasonable timeframes for doing the work, and useful reporting requirements. I will point out that the identification of five flood-prone areas in each borough is highly arbitrary and doesn’t reflect the reality of the city.

With respect to Intro 815, we believe that the maps we have published are robust and informative, so the legislation need only require that they should be maintained and updated as necessary. If the council has specific concerns with those maps, I’d be happy to discuss them. Further, I’d point out that DEP, not MOCEJ, is the right agency to manage floodmaps.

The other item in 815 is the idea that building code changes may be needed to address stormwater challenges. Given what I have said about the need for building-level resilience, I completely agree with this idea, but we are highly concerned that the approach 815 takes to this is premature and may be counterproductive. As a result, we must oppose Intro 815 as it stands, but we are willing to work with the Council to amend it if the Council is willing to allow enough time to do so.

I would like to use Intros 814 and 815 as an opportunity to streamline existing reporting requirements. MOCEJ in particular, and DEP as well, are subject to a long list of reporting requirements with inconsistent reporting dates, multiple reports on similar topics, and permanent reporting requirements that have long since outlived their usefulness. We are wasting scarce staff time in writing reports that no one reads, and we need to get out of that business so we can actually do the policy and engineering work to make progress.

As I have noted, we continue to need help getting our fair share of federal and state funding, so, while the Administration does not traditionally opine on council resolutions, I will say that Resolution 144 is consistent with messages I am trying to convey and can only help the City’s cause.

Above all, we need the City Council to help us think about this difficult tradeoff we will have to decide upon as a city: how much resilience are we willing to pay for, and how much inconvenience are we willing to impose on homeowners and building owners?

Thank you