Testimony of NYC Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Rohit T. Aggarwala

November 21, 2024

NYS Assembly Hearing Environmental Conservation Committee; Chair: Deborah Glick; Topic: PFAS; Location: Assembly Hearing Room B, Legislative Office Building, Albany

Good morning. Thank you for the invitation to speak today about PFAS contamination. My name is Rohit T. Aggarwala. I am the Chief Climate Officer in New York City, as well as the Commissioner of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

The City and DEP applaud Chair Glick for this hearing and her own efforts to combat forever chemicals with her Packaging Reduction and Recycling Improvement Act, and her Beauty Justice Act—which seeks to get harmful contaminants like PFAS out of cosmetics and other consumer personal care products—as well as many other bills that have passed through this committee focused on removing PFAS and forever chemicals from our environment.

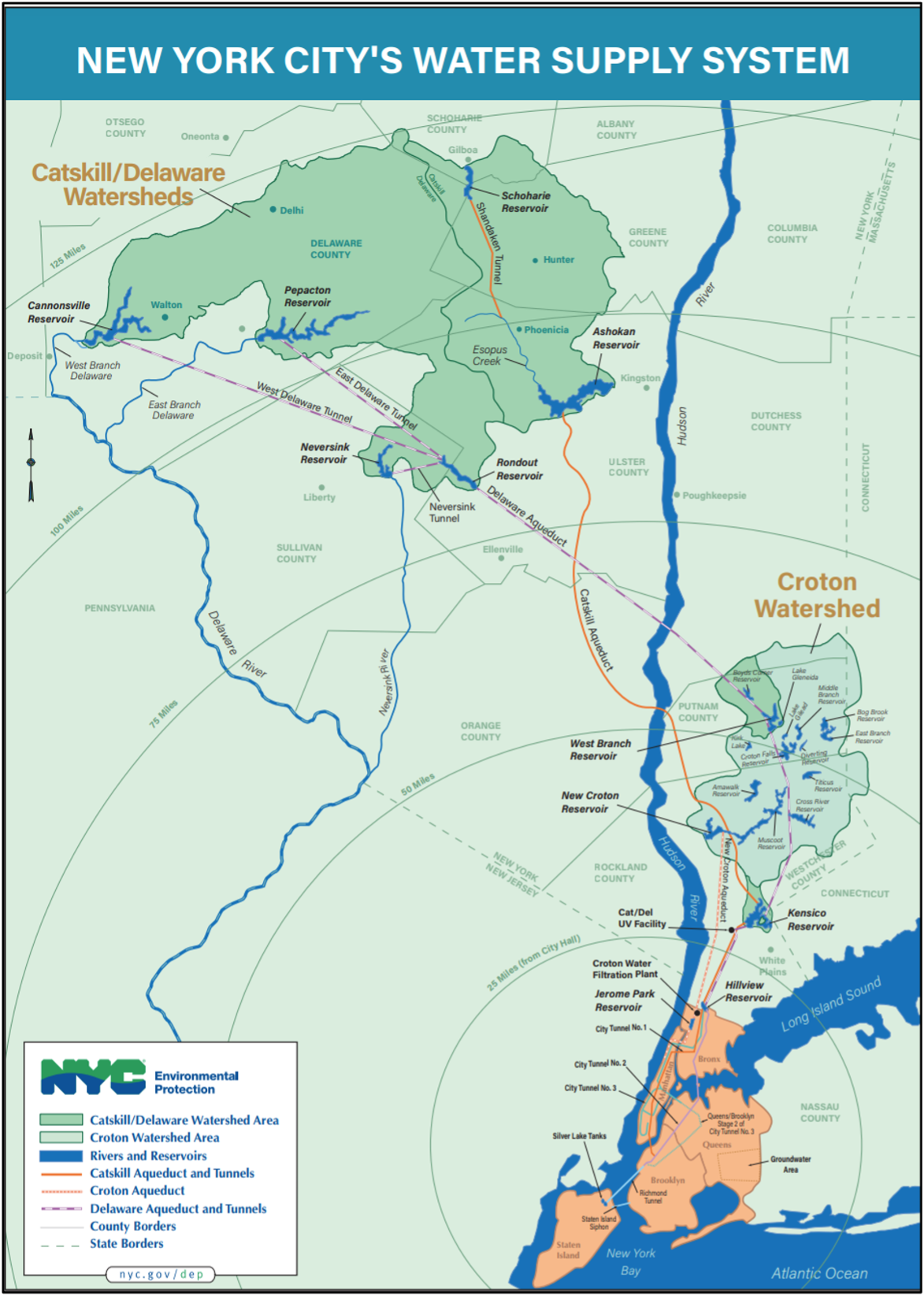

DEP manages New York City’s water supply, providing approximately 1 billion gallons of high-quality drinking water each day to nearly 10 million residents—about half of the state’s population—including 8.3 million in New York City and more than a million residents north of the city. The water is delivered from a watershed that extends more than 125 miles from the city, comprising 19 reservoirs and three controlled lakes. Approximately 7,000 miles of water mains, tunnels and aqueducts bring water to homes and businesses throughout the five boroughs and 7,500 miles of sewer lines and 96 pump stations take wastewater to our 14 in-city treatment plants. These Wastewater Resource Recovery Facilities (WRRFs) treat approximately 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater every day, turning it into clean water, biosolids, and biogas.

DEP also protects the health and safety of New Yorkers by enforcing the Air and Noise Codes and asbestos rules, and maintaining a police force dedicated to protecting our drinking water supply watershed and critical infrastructure. The agency has approximately 6,000 members on staff, including about 1,000 staff members who work north of the city in the Bureau of Water Supply and the DEP Police unit.

DEP is primarily a water utility. We treat water to provide it safely to our communities, then treat wastewater to return it safely to our waterways. PFAS are a concern throughout this entire cycle but it must be clear to everyone that water utilities such as DEP are passive receivers of PFAS, not the producers. And the best way to eliminate PFAS from our environment is to eliminate it at the source, which is manufacturing.

It should not become the responsibility of water or wastewater utilities to clean up the mess that industries have manufactured.

NYC’s Drinking Water Supply

As I mentioned, DEP’s watershed is located in counties north of the city.1 The water supply comes from a network of 19 collecting reservoirs upstate, ranging from Kensico in Westchester to Schoharie and Cannonsville, each more than 100 miles away from the City. The water supply systems date as far back as 1842.

Since the early 19th century, state law has given New York City the authority to regulate certain polluting activities to keep the water clean. For decades, we have been implementing regulations and partnering with residents and businesses to minimize the potential for pollutants to enter the system.2 Strong relationships between DEP and key water supply stakeholders including watershed communities, locally-based organizations, environmental groups, and federal, state, and local government agencies have been essential to the success of our source water protection efforts.

One cornerstone of the protection program is our land acquisition program, which permanently protects high priority sensitive lands in the Catskill/Delaware watershed. When the reservoirs were constructed, the City purchased about 78,000 acres of land. Since 1997, we have tripled our footprint, purchasing an additional 155,000 acres in the watersheds as buffer lands for water quality protection. As of December 2023, 39.8% of the Catskill/Delaware watershed land area as been permanently protected by the City, the state, and others. One effect of our land acquisition program, combined with our partnerships with local communities and the rural characteristic of the Catskill/Delaware watershed, has been that industries that may produce PFAS have stayed out of the area.3

Before I continue, I want to be sure to mention how proud we are to be part of these communities north of the city. We are a landowner, a major employer, a police force, and even the largest taxpayer in many counties. As such, we are very focused on making sure we are good neighbors. We maintain areas open to recreation, our police department assists with area emergency responses (including, recently, battling wildfires), and, whenever possible, we consider community feedback as we assess policies.

PFAS and Drinking Water

DEP tests New York City’s drinking water hundreds of times each day, 365 days a year.4 Testing is done throughout the water supply system, from the furthest reservoirs to street-side sampling stations that allow testing from city water mains. Our robust testing protocols have included PFAS sampling throughout the watershed as part of an emerging contaminant monitoring program, as well as in the distribution system for regulatory compliance. Earlier this year, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a series of PFAS regulations, including the first national drinking water standard for PFAS in drinking water, but we had already been focused on this issue. 5

We do not have a PFAS issue in our water supply. The majority of the water supply is usually drawn from the unfiltered Catskill-Delaware (CAT-DEL) system. We have never detected PFAS at critical locations in this system, either in the water leaving the Kensico Reservoir or at the distribution system entry points for the CAT-DEL system. PFAS has been detected in water from the smaller Croton System in 2021 and 2024, but the detected levels have been well below state and federal Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for drinking water.6

DEP’s Bureau of Water Supply is at the forefront of monitoring for PFAS in water supply. We have not waited for regulations to require us to act, and we will continue to conduct monitoring and research at key locations in the watershed to ensure that we meet current and future regulations. In addition to monitoring efforts, DEP has proactively hired a consultant to evaluate potential sources of PFAS in and around key locations in the supply system.

We do not have an issue with PFAS now, but we must continue to diligently monitor for PFAS as well as other potential pollutants. As I have said, these chemicals are becoming ubiquitous in the environment.7 They are found in rainwater, which fills our lakes and reservoirs, meaning that despite our stellar record to date, rain or surface water could one day introduce PFAS into our water supply. To protect our water supply, PFAS must be addressed at the source of the pollution. As long as PFAS are manufactured, there is potential for exposure. DEP’s robust watershed protection program has helped us avoid PFAS contamination, but that is not the case in other jurisdictions, and it may not be the case forever. Currently, we do not have treatment processes in place to remove PFAS from our unfiltered drinking water supply. We must keep them out of the supply, which means we must stop manufacturing them.

PFAS and Wastewater Treatment

DEP also collects wastewater from across the city and treats it to release clean water into the city waterways.8 The treatment includes a combination of biological and chemical processes. The treatment is effective and New York City’s waterways are the cleanest they have been in nearly 150 years.9 While treatment removes a wide array of pollutants and pathogens,10 it does not remove PFAS.

Wastewater Resource Recovery Facilities (WRRFs) are not a source of PFAS. The wastewater treatment process does not create PFAS, but because PFAS are in so many household products, there will be some background levels coming into WRRFs from domestic sources, along with industrial sources. These PFAS that come into the WRRFs pass through the treatment process and remain present in the clean water and the biosolids that are created by the treatment process.

WRRFs have been floated as an opportunity to address PFAS in the water cycle, but DEP and our colleagues in the wastewater treatment field strongly oppose relying on wastewater treatment for this purpose, as it would be prohibitively expensive and would have relatively little impact. If DEP were to be held responsible for treating PFAS—which are created by private industry—it would significantly impact operations (and costs) because of the advanced treatments that would be required. These costs would be borne by ratepayers instead of by the private industry that should be held responsible.

The cost is not the only complication. Testing and treating PFAS is still an emerging science. The EPA approved testing method for wastewater and solids is relatively new and not many labs have been certified in the method. Testing is expensive and appropriate tests are not yet available at cost-effective scale. Some advanced treatment options (e.g., pyrolysis with thermal oxidizer after-treatment) may break PFAS compounds down, but are expensive, energy intensive, and not yet at a scale appropriate to DEP’s operations.

Misplaced PFAS policies could also put at risk the beneficial use of biosolids, the nutrient-rich materials that are produced through a wastewater treatment process. Biosolids are soil-like materials that are full of nutrients that improve the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soil. Biosolids can be used to make soil healthier, promote crop growth, and re-vegetate mining sites. The DEP wastewater treatment process produces 1,300 wet tons of solids every day. These can be processed and used for composting or other purposes. Beneficial use of biosolids allows the carbon and nutrients to continue as part of the natural cycle among plants, animals (including humans), and the earth. Responsible land application of biosolids has tremendous climate benefits and is considered net carbon negative, not only for the carbon sequestration it provides, but also for the avoided manufacturing of unsustainable, synthetic fertilizers. Ironically, if biosolids are regulated for PFAS, they would be held to higher standards than chemical fertilizers which could also contain PFAS. The Climate Action Council’s Scoping Plan specifically calls out beneficial use of biosolids as a strategy to mitigate the worst effects of climate change. We are loathe to abandon such a program without a scientific basis.

If biosolids are not beneficially used, they must be landfilled and would eventually release greenhouse gases. Landfilling does not destroy PFAS. The PFAS would end up in leachate and without further treatment would again cycle around the environment and continue to accumulate. The benefits of using biosolids would be lost, and the PFAS problem would still exist.

The only practical way to reduce or eliminate PFAS from wastewater streams is to stop PFAS from entering the system by regulating the manufacture of PFAS.

Legislation

As noted earlier, there have been many bills in this committee focused on stopping PFAS at the source, and we applaud those efforts. Bills to eliminate PFAS and forever chemicals in packaging materials, cosmetic products, anti-fogging sprays and wipes, medical adhesives and bandages, playground surface materials, firefighting foam, cookware, and water-resistant clothing could all go a long way in reducing the amount of PFAS that water utilities receive in our drinking water supplies and in our wastewater.

Generally speaking, we are supportive of any legislation that recognizes that PFAS must be stopped at the source, and would be concerned about any legislation that punishes water utilities who are simply the passive receivers of these substances.

It’s also important to establish the tremendous climate benefits of using biosolids—a product of wastewater treatment—as a renewable alternative to synthetic fertilizers. Using biosolids as fertilizer reduces our use of landfills, reduces greenhouse gas emissions, improves soil health, and allows us to reuse the water we receive.

DEP is supportive of the enacted DEC interim biosolids strategy: DMM-7. This industrial pre-treatment approach implements a testing plan and aims to identify and mitigate industrial sources of PFAS entering wastewater facilities. It also sets limits on PFAS concentrations for biosolids, allowing for responsible land application. This approach has been successfully implemented in Michigan. In 2018, Michigan tested samples from 162 municipalities and identified six as being “industrially impacted” with PFAS concentrations above ambient. Following industrial pretreatment methods to deploy upstream source control, all six were able to identify upstream industrial sources of PFAS and significantly reduce their impact.11 DEP has a long history of success with its industrial pretreatment program. Industrial pretreatment has reduced total metals loading from industrial sources by about 75% over the past 25 years. We believe PFAS should be addressed in a similar manner.

DEP is also tracking emerging contaminant regulations that are being proposed under NYS Public Health Law Section 1112.

The proposed regulations would require water suppliers to notify the public within 90 days when certain PFAS compounds are detected in the distribution system. While DEP supports monitoring and transparency for emerging contaminants, this proposal would:

- require notifications for compounds that lack health-based MCLs.

- require notifications at concentrations below the levels at which laboratory results can be accurately reported.

- establish an unprecedented use of Public Notifications and create a new Tier for state notifications (in that Tier 2 requires notification within 30 days, and Tier 3 requires notification within one year under existing NYS Public Notification requirements).

- cause duplicative and confusing reporting to consumers since positive results are already included in water supply Consumer Confidence Reports, which are already moving from annual to biannual for systems serving 10,000 or more persons.

Essentially, the proposal places the burden on passive receivers, does nothing to eliminate PFAS from the environment (including drinking water), and will undermine public confidence in NYC drinking water.

DEP is also supportive of federal efforts to protect water utilities like ourselves in the face of PFAS regulation, for example the Federal Water System PFAS Liability Protection Act (S. 1430, HR. 7944). That legislation exempts public water systems from liability under CERCLA for release and mitigation of PFAS from wastewater treatment facilities, recognizing appropriately that water systems are not the source of PFAS.

Thank you very much for the opportunity to testify at this hearing. We look forward to working with this committee and our other partners in State, Federal and City government to amplify each other’s efforts in protecting the public and public water supplies like DEP from PFAS and other forever chemicals.

1More information about the DEP watershed can be found on the DEP website: https://www.nyc.gov/site/dep/environment/about-the-watershed.page

2More information about programs for businesses and communities can be found on the DEP website: https://www.nyc.gov/site/dep/environment/programs-for-communities-businesses.page

3More information about DEP’s watershed protection programs can be found in recent testimony before the NYC Council, which can be found on the DEP website: https://www.nyc.gov/site/dep/news/102824/testimony-rohit-t-aggarwala-commissioner-new-york-city-department-environmental-protection

4Information about DEP drinking water testing can be found in the annual New York City Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/dep/downloads/pdf/water/drinking-water/drinking-water-supply-quality-report/2023-drinking-water-supply-quality-report.pdf

5Key EPA Actions to Address PFAS | US EPA

6Westchester Airport has been identified as a potential PFAS source, because of the firefighting equipment required at airports. Westchester Airport is under a DEC consent order for PFAS remediation. We are seeing positive results in the feeding streams in that area.

7Ocean spray emits more PFAS than industrial polluters, study finds | PFAS | The Guardian

8https://www.nyc.gov/site/dep/water/wastewater-treatment-system.page

9https://www.nyc.gov/site/dep/water/harbor-water-quality.page

10https://www.nyc.gov/site/dep/water/wastewater-treatment-system.page

11Land Application of Biosolids Containing PFAS Interim Strategy Updated 2022