Testimony of Vincent Sapienza Chief Operating Officer New York City Department of Environmental Protection before the New York City Council

December 1, 2022 — Oversight Hearing The Billion Oyster Project and Nature-Based Solutions

Good afternoon, Chair Kagan and the Members of the Resiliency and Waterfronts committee. My name is Vincent Sapienza; I am the Chief Operating Officer at the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). I am here today to speak about some of DEP’s nature-based solutions for various challenges that the city has been facing. DEP has long-standing nature-based infrastructure programs. In fact, DEP is running one of the most advanced nature-based programs in the country.

DEP’s green infrastructure (GI) and Bluebelt programs are designed to manage stormwater. The first goal of the program was to improve harbor water quality by keeping stormwater out of combined sewer systems during rain events. This management reduces the volume of wastewater that might have to be released untreated during rain events, keeping pollutants out of the waterways. Newer GI systems are focused on managing stormwater in areas that are prone to flooding. DEP’s most common stormwater management tools are Green Infrastructure and Bluebelts, so I would like to tell you a little bit about both of these programs.

Green Infrastructure

Green infrastructure collects and manages stormwater outside of the traditional stormwater sewer system. They use or mimic nature. By absorbing stormwater before it enters the sewer system, GI reduces the amount of untreated wastewater and stormwater that could contributed to combined sewer overflows.

GI comes in many forms and ranges in size from rain barrels at individual homes to uncovering streams that have long been buried underground. I would like to take a minute to walk you through some of the most common types of GI we have in the city.

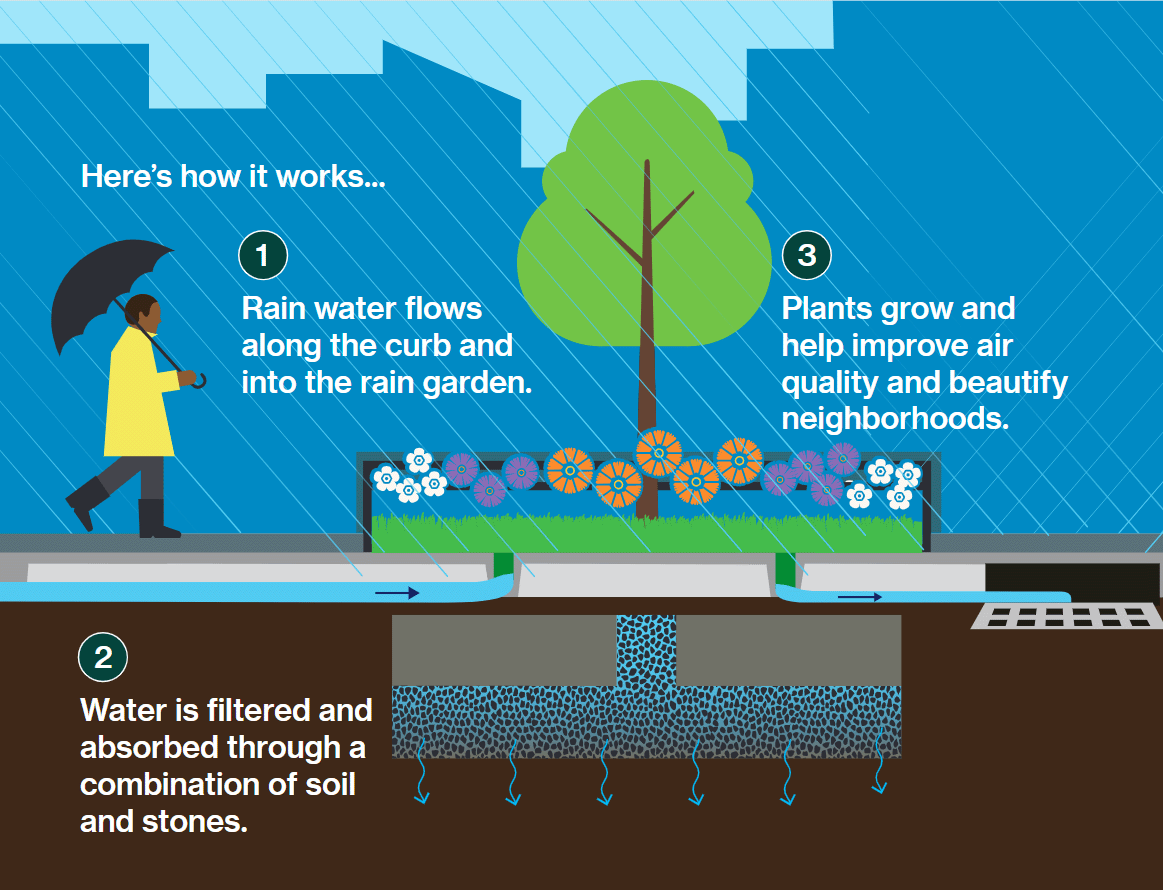

- Rain Gardens, Stormwater Greenstreets, and Infiltration Basins

These three systems look different on the surface but have similar below ground engineering to capture stormwater. Each of these installations, or assets, allows water to flow in and then seep through layers of engineered soil and stone into the ground underneath. This process is called “infiltration.”

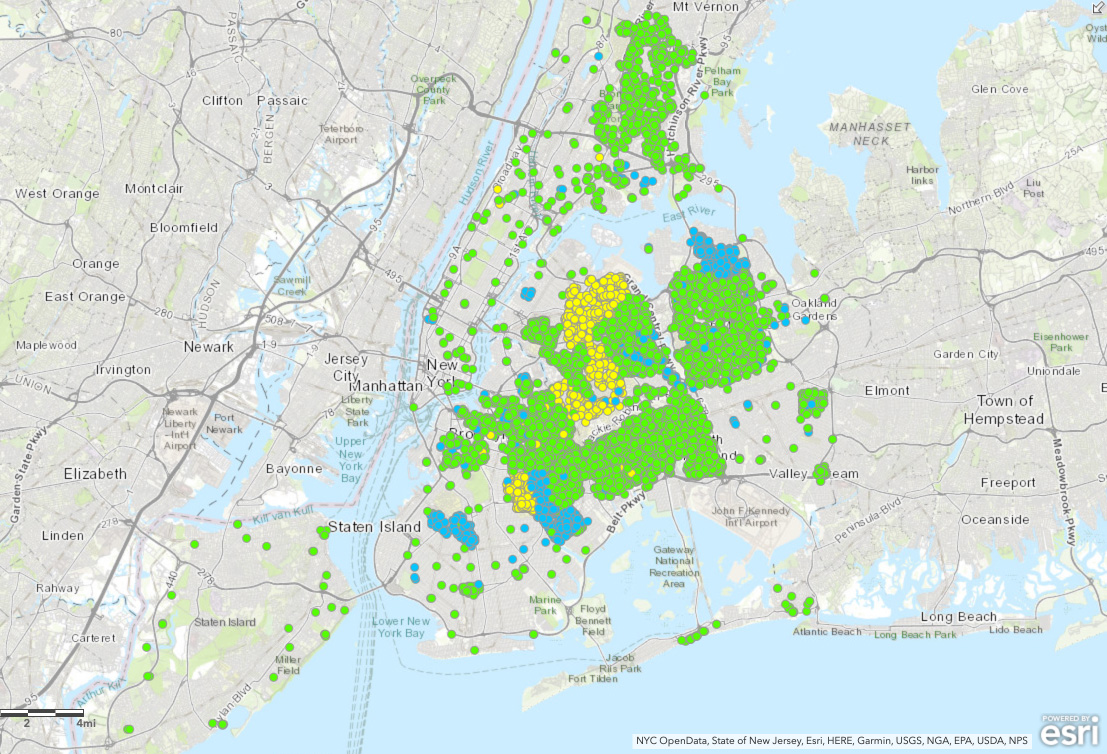

Since 2011, DEP has constructed more than 11,000 of these infiltration assets, “greening” more than 2,000 acres around the city.

DEP GI Program Map

DEP GI Program MapRain gardens and stormwater greenstreets have vegetative tops, whereas infiltration basins are installed without gardens, so the tops look like grass or sidewalk.

Rain Garden in Rego Park, Queens

Rain Garden in Rego Park, Queens Infiltration Basin

Infiltration BasinStormwater greenstreets are the largest of these assets. They are located in roadways instead of on the sidewalk, so they can vary in size and depths as the location allows.

Stormwater Greenstreet

Stormwater Greenstreet - Green Roofs

Green roofs are rooftops that have been designed to capture and retain stormwater. These roofs are different from simple rooftop gardens because they have engineered soil and drainage layers to maximize rain absorption.

Green Roof at Brooklyn Navy Yard

Green Roof at Brooklyn Navy Yard - Blue Roofs, Subsurface Detention Systems, and Rain Barrels

Each of these asset types function by catching and storing stormwater. Unlike the systems I just mentioned, these assets do not immediately infiltrate water through soil systems. They hold water in place until the rain event has passed and then release it gradually.

Blue Roof in the South Bronx

Blue Roof in the South BronxRain barrels work on smaller scales. They are connected to the existing downspout of a roof and collect water that homeowners can later use for watering plants and other landscaping. DEP works with elected officials and community organizations to hold rain barrel distribution events each summer. We have already partnered with many of your offices to distribute rain barrels and look forward to more events in 2023.

Rain Barrel Distribution

Rain Barrel Distribution - Permeable Pavement

Traditionally, paving an area makes it “impermeable,” meaning water cannot drain through it. This is why water is absorbed by dirt but flows off of streets. Permeable pavement, however, allows water to seep through to the ground, where it can be absorbed. Areas with permeable paving have less stormwater runoff than areas with traditional paving.

In particular, we have been expanding porous pavement, which is one type of permeable pavement. Porous pavement is special roadway paving that is designed to collect and manage stormwater that runs off the streets and sidewalks when it rains. Typical installations include porous concrete panels in the parking lanes in non-commercial areas.

Porous pavement in parking lane

Porous pavement in parking laneOverall, GI uses rainwater as a resource instead of treating it as waste. These systems help the sewer system function more effectively, keeping our harbor waters clean and helping reduce ponding on the streets. Assets like rain gardens also provide shade, cool and clean air, provide habitats for wildlife, and beautify neighborhoods.

- Bluebelt

Bluebelts are networks of engineered waterbodies that capture and treat stormwater. They preserve natural drainage corridors such as streams, ponds, and wetlands, and connect them to new storm sewer networks. These systems mitigate street flooding while improving water quality and ecosystem health. Some Bluebelts detain water from the sewer network and then slowly drain back into the sewer system when the rain event has passed and the system has the capacity to manage it. Other Bluebelts near shores provide stormwater storage then release water into the harbor when the tide goes out. Bluebelts allow DEP to provide proper street drainage without expensive pumping.

Because Bluebelts use wetlands and ponds to manage stormwater, they are primarily sited at locations with existing waterbodies and separate storm sewer networks. Most of them are on Staten Island because Staten Island has more intact watercourses and waterbodies than the other boroughs. Over the last ten years DEP has built Bluebelts for approximately one third of Staten Island’s land area. DEP has also created some Bluebelts in Queens and is looking to expand the program in other boroughs.

Bluebelt, Staten Island

Bluebelt, Staten IslandBluebelts are true community assets. In addition to reducing flooding and improving water quality, they provide open green space landscaped with native vegetation and diverse wildlife. They provide benefits to communities beyond stormwater detention. As we face rising sea levels and heavier and more frequent rain events, Bluebelts offer a natural and effective solution for stable and sound stormwater management.

Looking Forward

For decades, New York and other cities have been growing by working against our natural surroundings, turning vibrant ecosystems into concrete jungles. We have finally come to understand that the most effective way to live in our environment is to embrace it and incorporate natural systems into our city infrastructure.

Even as we expand our stormwater sewer network in some areas, we are focused on new and innovative solutions, including nature-based solutions. These tools are important because there many challenges that traditional (gray) infrastructure alone cannot meet. They are key to preparing the city for the future.