Testimony of Vincent Sapienza Commissioner New York City Department of Environmental Protection before the New York City Council Committee on Resiliency and Waterfronts Committee on Parks and Recreation

October 20, 2021

Good afternoon, Chair Gennaro, Chair Brannan, Chair Koo, and members of the Committees on Environmental Protection, Resiliency and Waterfronts, and Parks and Recreation. My name is Vincent Sapienza; I am the Commissioner of the NYC Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Thank you for the opportunity to speak today about the topics of combined sewer overflows, green infrastructure, and urban flooding. These issues are critical to the work of DEP and our mission to enrich the environment and protect public health for everyone who lives and works in New York City.

As many of you are aware, DEP delivers approximately 1 billion gallons of drinking water each day from a watershed that extends more than 125 miles from the City. In addition, we maintain over 7,000 miles of water mains, 7,500 miles of sewer mains, 96 pump stations and 14 in-City wastewater treatment plants. While the water and wastewater system was built as a marvel of engineering creativity and determination, this critical infrastructure was built for a vastly different climate reality. Our team continues to make systematic improvements, planning for a wetter future while balancing several different goals. We are simultaneously reducing combined sewer overflows to improve harbor water quality, mitigating flooding to reduce property damage and protect human life, and maintaining a state of good repair to ensure longevity of our infrastructure. I commend all our staff for what they have accomplished over the years and recognize that we still have much more to do.

A Changing Climate

There is a saying that “Climate Change is Water Change.” A warmer climate impacts nearly every facet of the water cycle which impacts nearly every facet of our work. DEP has always designed our systems with built-in redundancy, flexibility, and design criteria for extremes. For instance, we know that an uninterrupted, clean drinking water supply is essential, and dating back over 100 years, planners and engineers considered the possibility of droughts and heavy rain events. As much as possible, our drainage systems are also sized for heavy rain—and while we know there are limits to engineered solutions for extreme events, we also recognize that there is an opportunity for innovation and progress.

Harbor Water Quality & Combined Sewer Overflows

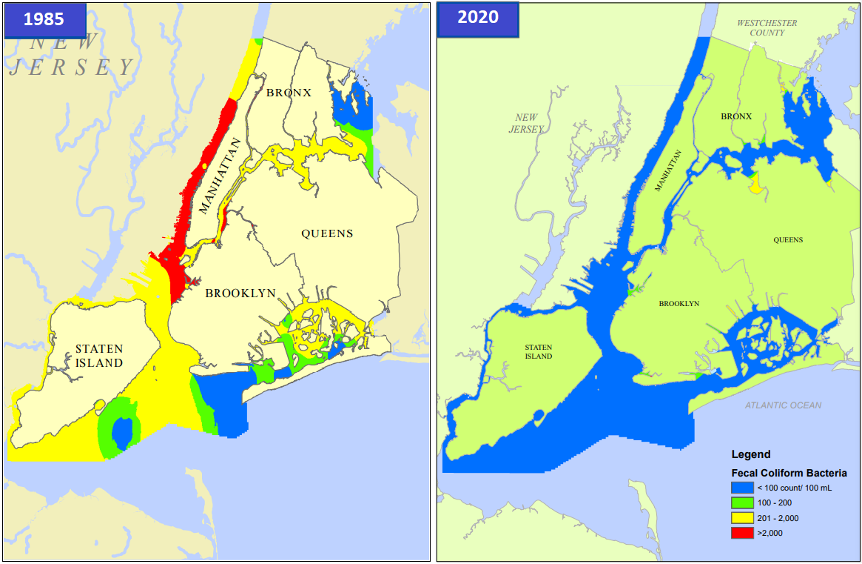

I will begin with a discussion about harbor water quality improvements and combined sewer overflows, or CSOs. Much of the city’s sewer infrastructure is a combined sewer system, which means the sewer collects stormwater and sanitary sewage in the same pipe. Many older municipalities have a similar system. This combination of stormwater and wastewater is carried to one of our 14 Wastewater Resource Recovery Facilities (WRRF) where it is treated, and clean water is released into the harbor. The City has invested billions in the design, construction and upgrade of critical wastewater infrastructure across all five boroughs. The results are astonishing, and we are proud to say that because of our investments, the waters surrounding New York City are cleaner and healthier than they have been in 150 years—since the Civil War. The improvements are apparent every time a seal, dolphin, or whale is sighted off our shores.

On a dry weather day, our WRRFs receive about 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater, and they have the capacity to treat up to 3.8 billion gallons a day. During some storm events, the volume or intensity of the rain can exceed the capacity of the local sewer network. When that happens, excess flow is diverted into a local open waterway, and that is known as a CSO. These releases are authorized by U.S. EPA and the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). The City has over 400 CSO outfalls throughout the five boroughs and they function as critical infrastructure, protecting the treatment process at the WRRFs and ensuring they continue to treat sewage consistently after the rain ends. They also help prevent stormwater and wastewater from backing up into homes and neighborhoods. These CSO releases, however, can hamper our water quality improvement goals, especially in constrained tributaries like the Hutchinson River and Newtown Creek. We remain dedicated to building off our successes and further reducing CSOs to improve water quality in these waterbodies.

In recent years we have spent nearly $3B in grey infrastructure projects like the Alley Creek CSO Storage Facility and the Gowanus Canal Flushing Tunnel and Pump Station Reconstruction. In 2012 we kicked off the Long Term Control Plan (LTCP) process with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and stakeholders to develop eleven Long Term Control Plans (LTCPs) for the waterbodies impacted by CSOs. The LTCP work is consistent with the Federal CSO Policy and the water quality goals of the Clean Water Act (CWA). Through this program we have committed more than $6B in projects that will further reduce the volume and frequency of CSOs for those waterbodies that do not achieve applicable water quality standards. Planning and design are already underway for many of these investments.

I want to emphasize that the capital costs for CSO reductions are not linear. While billions have been spent so far, it would take tens of billions to eliminate CSOs. As a result, we have embraced a hybrid approach to CSO reduction, strategically incorporating grey infrastructure which is energy intensive and expensive to maintain and balancing it with green infrastructure which makes our city more permeable and we absorb rain right where it falls. We believe this hybrid approach is a much more sustainable and cost-effective path forward.

Green Infrastructure

One important component of CSO reduction is Green Infrastructure (GI) with a goal of reducing CSOs by 1.67 BGY. GI is engineered to absorb or hold stormwater on site, preventing that water from entering the traditional sewer system. Keeping storm volume out of the sewers reduces stress on the WRRFs and cuts CSO into waterways.

New York City has implemented the most aggressive green infrastructure program in the country. In just the last decade, our GI program has:

- Constructed more than 11,000 assets,

- Managed more than 1,500 acres,

- Added more than 660,000 square feet of pervious surfaces to streets and sidewalks, and

- Created more than 14,000 acres of Bluebelts across the city.

Many of the projects have been done in partnership with other city agencies, including the Department of Transportation, Department of Parks and Recreation, NYCHA, and schools.

GI takes many forms. The suite of options allows us to use the best options for each geography. GI includes large projects like Tibbets Brooks daylighting, and small distributed projects like rain gardens, infiltration basins, stormwater green streets, green roofs, blue roofs, permeable pavement, subsurface detention systems, and rain barrels and cisterns. Work is not confined to combined sewer areas. We have built more than 70 Bluebelts across Staten Island and are expanding the program into Queens and the Bronx.

All of these projects are engineered to make land and buildings more efficient at managing stormwater runoff. Rain gardens in the sidewalks have been our most widely used tool and, in addition to carefully designed vegetative palettes at their surface, they involve specially engineered systems installed below the surface. The subsurface structure is designed to store and then slowly percolate the captured runoff into the ground. This subsurface feature is the most critical part of a rain garden and what distinguishes them from standard street tree pits; it also makes them much more difficult to construct. Rain gardens are not feasible in locations with bedrock or a high water table or where other utilities or street and sidewalk infrastructure prevent us from using the space for stormwater management.

Where rain gardens are not feasible, DEP has been working with NYC DOT on the installation of permeable street pavement to absorb runoff. As noted in the Extreme Storms Management report that the Mayor released last month, we are now significantly accelerating the use of permeable pavement.

In addition to the work that DEP does directly, we encourage others to implement green infrastructure through financial incentives. The green infrastructure grant program funds the design and construction of green roofs on private property. Most recently, the Brooklyn Navy Yard added more than 23,000 square feet of green roof with funding from the grant program. To date, we’ve provided more than $13M to 33 private property owners for green infrastructure. We’ve also kicked off a $53M contract to retrofit privately owned large impervious properties with green infrastructure.

We are also developing a Unified Stormwater Rule (USWR), which will require more on-site stormwater management for new and redeveloped properties that connect to the city’s sewer system. The unified rule will also require green infrastructure implementation on redeveloped lots that are 20,000 SF or larger or create 5,000 SF or more of new impervious area, leading to more pervious and resilient properties across the city. While the primary goal of the GI program is to reduce CSOs in a cost-effective way, the projects also provide community and environmental benefits. These “co-benefits” include increased urban greening, urban heat island reduction, and more habitat for birds and pollinators around the city.

Flooding

While the total amount of annual rainfall on the city has not changed much in the past two decades, it is apparent that climate change is causing more significant brief downpours or cloudbursts. Our sewers were designed to handle lots of runoff, but not all at once. Intensity is what causes flooding.

Simply replacing existing combined sewers with bigger, deeper ones is imprudent. We must take a holistic approach to reduce flooding. Our current four-year capital plan includes $2.3B for 278 projects to improve drainage that includes new tools like non-networked ‘high-level’ storm sewers and expanding our GI programs.

As Director Bavishi mentioned, we are collaborating with the Mayor’s Office and our agency colleagues on innovative solutions to cloudburst flooding. We already have three cloudburst projects in Queens that are in the design phase, one with NYCHA in the South Jamaica Houses and two in St. Albans. We are supporting the effort to identify cloudburst neighborhoods by performing a physical and social vulnerability assessment which will be followed by engineering feasibility study for cloudburst neighborhood opportunities. We look forward to working with you all and external stakeholders across the City as this program develops.

Legislation

Finally, I want to speak to the bills being heard today. We appreciate the importance of the issues raised by these pieces of legislation and look forward to working with the Council to address critical needs across the City.

- Intro 1618 would require DEP to report on progress towards reducing pollution in City waterways that is caused by combined sewer overflows and stormwater runoff. We would like to work with the Council to ensure this bill aligns with current DEP reporting requirements. For example, DEP provides quarterly updates on LTCP implementation, reports on CSO discharges each year through an Annual CSO BMP Report, and submits yearly progress updates on water quality improvement strategies in the Green Infrastructure Annual Report and the Stormwater Management Program Annual Report. All of these reports are submitted to the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation and are available to the public on the DEP website. Water quality data from our Harbor Survey Monitoring Program is also available on NYC Open Data.

- Intro 383 would require DEP to submit an annual report on drainage infrastructure. As with 1618 we would work with the Council to ensure that this bill does not conflict with existing state and federal reporting. For example, DEP already complies with the State Pollution Discharge Elimination System, or SPDES, permits and applicable law, by reporting to the State and the Public, discharges of untreated or partially treated sewage using the State's approved electronic public notification system—NY-Alert.

- Intro 67 would place liability on the City for sewer service lines and require the City to develop a plan to mitigate and prevent sewer backups. DEP has done extensive work to reduce sewer backups and SBUs are down 70% over the past decade. We regularly report to the EPA on our progress and also release an Annual State of the Sewers Report, which is available on the DEP website. We have initial concerns about the fiscal and legal ramifications of shifting liability of sewer service lines to the City and we are still reviewing with the Law Department and OMB.

- The unnumbered preconsidered intro would require DEP to establish a program to provide financial assistance for the purchase and installation of backwater valves. We agree with Council that backwater valves can be an important tool in the toolkit homeowners need to reduce flooding on their property. While DEP does have experience providing financial assistance for home upgrades through our Toilet Replacement and Rain Barrel Giveaway Programs, providing assistance for backwater valves is of a different nature. We will need to consider this proposal with the Law Department and the Office of Management and Budget before committing to a citywide backwater valve program. We look forward to engaging on this with Council and sharing the results of MOCR’s backwater valve study, which will become available next year. This study will review where backwater valves will be most effective and consider equity and cost as it relates to prioritized implementation.

- Intro 2168 would require DEP to create a searchable database that would allow members of the public to access private customer information. Implementation of this bill would make customer data available to third-party entities without consent. This would result in a serious breach of customer privacy and does not align with industry best practices. Ensuring customer privacy is an important safety measure particularly for vulnerable homeowners whose presence at home could be tracked by these third-party entities. We are also concerned that customers with large debts could be targeted by predatory actors who could access their account information. Protecting customer water and sewer data is a critical guiding principal in the development of our new billing system which launched last month. This system is not designed to be searchable by the public, however, customers can designate a third-party delegate to access their billing information. We will gladly sit with the council to discuss our concerns about this bill in more detail once the Law Department has thoroughly reviewed it.

- Lastly, I recognize that Intro 2425 and Int. No 1845-A were both recently added to today’s agenda. These bills would require DEP to create Borough Commissioner positions and to inspect catch basins annually. We look forward to reviewing the language more closely and following up with you.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify here today. Before I close, it’s important to remind everyone that the City’s drainage infrastructure is funded directly from water bills that all New Yorkers pay, whether directly or indirectly. Each spring, DEP consults with the City Council on our expense and capital needs for the coming fiscal year, and each year we hear public testimony about the impact of rising water rates on finances for families and small businesses. We must continue to make strategic investments while maintaining affordable rates, minimizing payment delinquencies, and supporting low-income New Yorkers, especially as we all continue to recover from the economic challenges of the pandemic. Without federal or state funding, we must prioritize and balance our long-term planning with public affordability. Again, we appreciate the Council’s commitment to working with us on these complex issues. My colleagues and I are now happy to answer any questions you may have.