Keeping a Dream Alive

January 20, 2025

On a Friday night in Harlem in September 1958, the area around the famed Hotel Theresa—affectionately known as the “Waldorf of Harlem”—bustled with energy. The crowd outside had gathered with a unified purpose: to push for further desegregation within the nation’s public and private schools.

African American luminaries such as Duke Ellington and Jackie Robinson addressed the audience before the booming voice of a generation, the most prominent leader of the Civil Rights Movement, took the stage.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s words cut through the evening air, condemning hatred and bigotry, especially in classrooms. The Atlanta native was on a multiday visit to New York City and, as the Friday event wound down, a member of King’s camp suggested that he have a bodyguard close to him during his stay.

Given his nature, and without pause, King dismissed the idea. It was a decision that may have cost him his life the very next day, had it not been for two alert NYPD cops from the 28th Precinct.

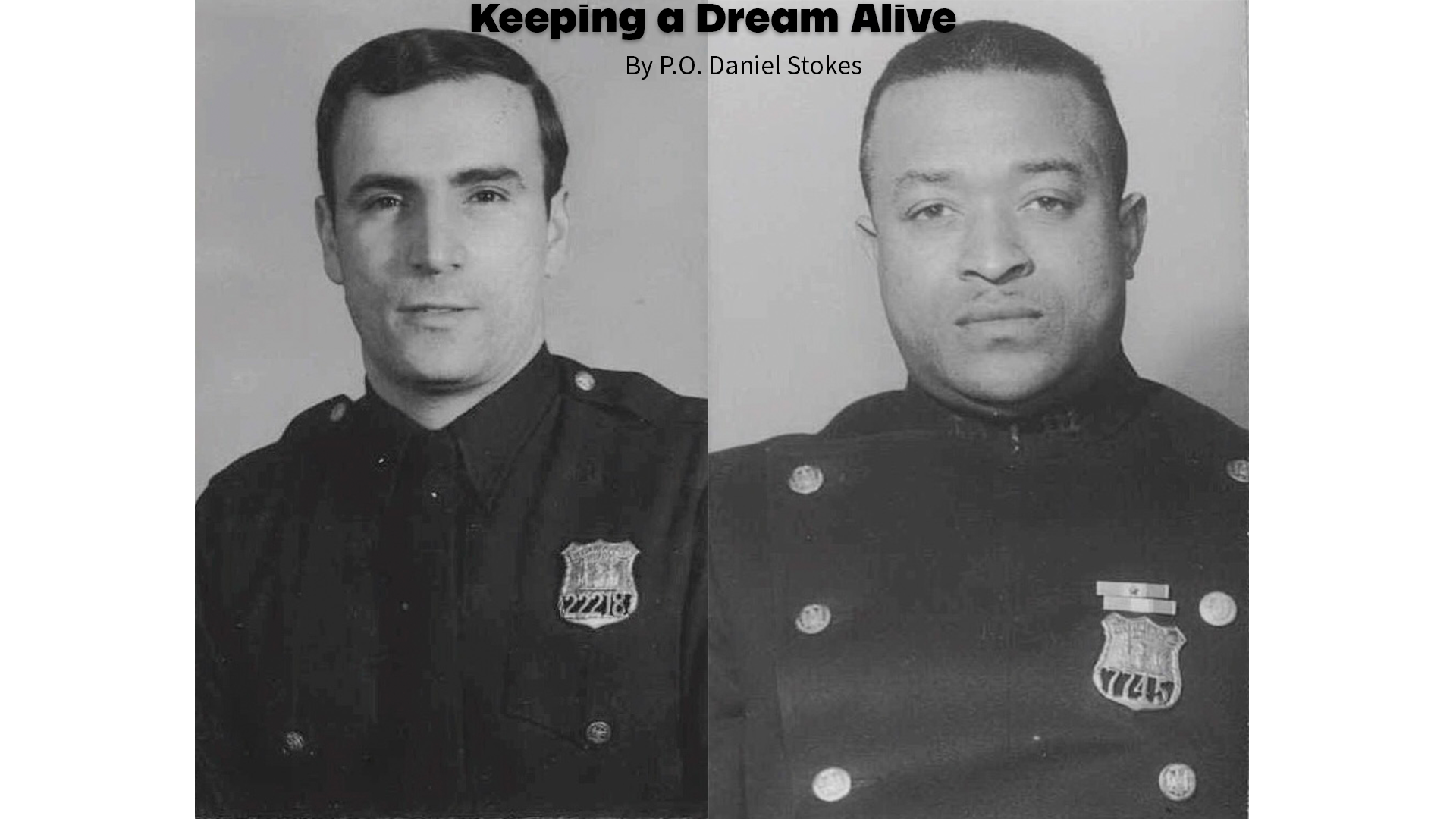

The afternoon sun shone brightly over Harlem on that Saturday, Sept. 20, and Patrolman Al Howard, a three-year veteran of the department, was behind the wheel of a marked radio car. Next to him sat Patrolman Phil Romano, fresh out of the academy, monitoring the vehicle’s two-way transmitter.

Shortly after 3 p.m., the two were dispatched to a disturbance in the vicinity of the Apollo Theater. Howard turned the car toward 230 W. 125th St., where chaos had just erupted inside Blumstein’s department store, where King was hosting a book signing on the second floor.

The officers entered the crowded store and observed a scene of utter chaos. King was sitting upright in a chair, calm but gravely injured, with a six-inch, steel letter opener protruding from his chest.

As blood seeped from King’s wound, a woman rushed forward and attempted to pull out the blade. Romano quickly intervened by pushing the woman’s hand away, and bluntly explained that removing the object could very well be what kills the preacher.

In “When Harlem Saved a King,” a documentary film made about the ordeal, Howard recalled, “I told [King] not to move. Don’t even breathe. I’ve never seen a person so calm in my life. He was like a saint.”

Police lacked portable radios at the time, so Howard used a telephone to summon an ambulance.

Then, he and Romano orchestrated an ingenious plan to get the injured civil rights leader out through the rear of the store by first announcing to the panicked—and growing—crowd on 125th Street that King would be coming out the front door.

With the crowd’s attention focused on the north side of the building, the men carried King—still seated in his book-signing chair—out the south side to West 124th St., then rode with him in the ambulance.

“I looked in his eyes and said, ‘We will get through this, I guarantee you,’” Romano recalled. “He looked at me and smiled.”

At Harlem Hospital, doctors carefully removed the letter opener and confirmed that it had missed King’s largest artery by a fraction of an inch.

Nearly 10 years after he was attacked in New York City—and just one day before he would be shot and killed while standing on a balcony outside his second-floor motel room in Memphis, Tenn.—King mentioned the book-signing incident in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” sermon at Mason Temple.

“That blade had gone through, and the X-rays revealed that the top of the blade was on the edge of my aorta, the main artery,” he told the congregation. “And once that’s punctured, you’re drowned in your own blood—that’s the end of you.

“It came out in the New York Times the next morning, that if I had merely sneezed, I would have died…. I’m so happy that I didn’t sneeze.”

In the moments following the incident at the New York City department store, Good Samaritans held King’s assailant for other responding officers. A woman with a history of mental illness, she claimed she had been “looking for” King for six years, according to news reports at the time. Police found a .25-caliber pistol tucked inside her bra.

Howard, who later helped to lead the NYPD’s investigation into the “Son of Sam” serial killings in the 1970s, retired as a sergeant in 1986 after 31 years of service. He became a pillar of the Harlem community during his post-NYPD days, owning and operating the historic Showman’s jazz club until his passing in 2020 at the age of 93.

Romano also rose through the ranks, retiring as a lieutenant in 1991 after 34 years of distinguished service.

Neither officer would ever forget their near-death experience with King—the minister and activist would make absolutely sure of that.

From his hospital bed in Harlem, King penned a heartfelt letter to the NYPD, praising the bravery and quick-thinking of Patrolmen Howard and Romano.

“I have long been aware of the meaning of the phrase ‘New York’s Finest,’” he wrote. “From the moment of my unfortunate accident, I have concurred, wholeheartedly, in that appellation. There are none finer.”