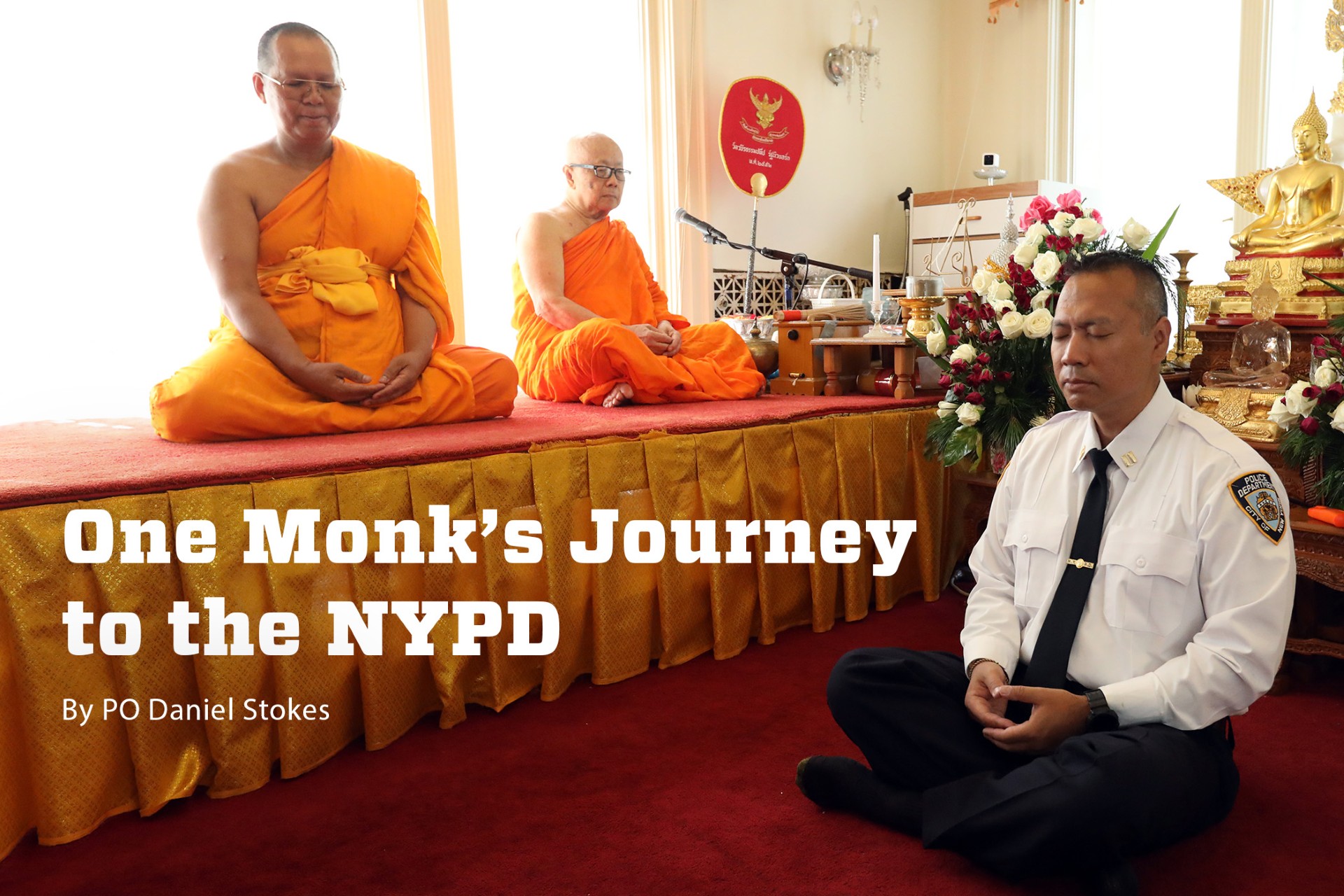

One Monk’s Journey to the NYPD

July 30, 2024

Daily strolls along mud-packed paths on the way to and from his Buddhist temple in Thailand were not immediately analogous to Captain Tawee Theanthong’s earliest assignment walking the beat in the sprawling South Bronx public housing developments of Police Service Area 7. Yet, both were paths of the righteous, Theanthong can now say, and both proved instructional in developing the virtues of patience and humility.

Before Theanthong joined the NYPD 21 years ago, and long before he was tapped to lead key positions in the Detective Bureau, he was just like most American kids growing up in the 1980s: Nikes on his feet and a video game addiction. But as the son of Thai immigrants, the Queens native longed to connect with his ancestral culture, traditions, and spirituality. He had already graduated from college, but didn’t have a plan for what came next. After much internal deliberation, and at just 22 years old, Theanthong decided to move to Thailand and become a monk.

“I didn’t have a plan,” Theanthong said. “I remember thinking that I’ve lived here (in the United States) my whole life and I say that I am Buddhist, but do I really know what the philosophy, religion, and meaning behind it is? I realized I didn’t know much. So I hopped on a plane to find out.”

After a journey of nearly 26 hours that included several layovers, Theanthong arrived at Don Mueang Airport in Bangkok. When the airport’s automatic front doors opened to welcome him to his ancestral home, he was immediately hit with what he described as an “oven-blast of heat.” It was the tropics of Southeast Asia, and it was far removed from New York City. A long-tail boat brought him up the Mekong River, to a canal, and then to a village of the same name: Mekong, the tiny hamlet where Theanthong’s father and grandfather had lived much of their lives.

“Buddhism is big on the concept of karma and building goodwill,” Theanthong said. “If I’m dedicating a good portion of my life to learning and teaching people Buddhism, it’s considered really good karma. And to be doing it in my grandfather’s village—it was also good karma for him.”

Traditionally, young men in Thailand might spend anywhere between one day to three months as a monk, leaving behind their family and the comforts of the material world to dedicate themselves to learning meditation, moral conduct, and the wisdom of Theravada Buddhism, commonly accepted as the oldest version of the Buddha’s teachings. Eventually, most return to the secular life better prepared to embrace careers and start families.

“You want to learn how to become a more moral, caring, and empathetic person,” Theanthong said. “The tradition wants you to become a monk with the thinking that you are still young and haven’t started a family yet. They want you to take those ideas and principles you learn from your time as a monk to your family.”

The ceremony to become a monk begins with the novice trading in their old clothes for a white robe, ambling through the temple in prayer as their relatives follow behind (a gracious way to see off loved ones), then having their heads and eyebrows shaved to the skin. Finally, the Chao Awat, the head monk of the monastery, replaces their white robe with another of the same saffron color worn by ordained monks. Once complete, the new monks are entrusted with new responsibilities, including presiding over weddings and funerals, and venturing to hospitals to pray with the sick, that their health may be restored and their lives extended. In addition to a robe, each monk is provided a razor to keep their head and eyebrows shorn, and a cast-iron alms bowl with a lid, used to gather one daily meal.

Police officers understand as well as anyone the importance of uniforms and uniformity: to encourage cohesion and teamwork, professionalism and preparedness, and to signal authority to the public when there is trouble. With their shaved heads and identical robes, there is uniformity among monks too, and yet their appearance is not intended to accentuate identity, but rather to strip it away—to erase the “me.”

“When you are born into this world, you are naked with no possessions,” Theanthong said. “And when you leave this world, you are going to be naked with no possessions. We don’t take anything with us to the afterlife. To want is to suffer; if you cut that off at its core—and the belief of the individual—then you don’t struggle with that as much.”

“Monks give themselves to their communities. Sounds a lot like being a cop, right?“

Theanthong recalled that during his first few nights at the temple, the Thai monks—even the young acolytes like him—believed the American kid would never make it.

“I thought the same thing,” he said. “I didn’t believe I would make it. I speak Thai fluently, but I couldn’t read or write it. Ironically, the books we read were in Sanskrit.”

Study of the ancient, sacred language remains an intrinsic part of monastic education in Thailand, and Theanthong struggled with it.

“But belief is a very powerful principal,” he said. “It’s amazing what people can do when they believe.”

Theanthong meditated and chanted, studied and reflected, completed all of his daily tasks and used his cast-iron bowl to eat the food he was provided by local villagers. His chanting in Sanskrit came along. And, after a time, it was clear that he would be just fine.

As his stay continued, Theanthong began traveling to other temples. He held the distinction of being the only American in the monastery, as well as the only monk from a western nation. But he wasn’t just a novelty. After he gave sermons on impermanence, identity, and trying to live more empathetically and compassionately, his fellow monks took notice of his capabilities and recognized a particular value.

“I was asked if I ever thought that I was brought here for a reason,” Theanthong said. “I was told that because I understood Buddhism so well, and that I’ve been doing this for a while, I had built up credibility, and people would listen because I speak English. ‘Imagine the audience that you can reach? Westerners come to these temples and you could be the voice of these temples.’”

The future NYPD executive, whose last name means “Golden Candle,” considered his fellow monks’ reasoning. He had already stayed well past three months, and would have stayed longer if it had not been for a phone call from his father.

“I remember him saying that I had learned a lot and that he was really proud of me,” Theanthong said. “But he didn’t think my job back home was done just yet. I wasn’t ready to devote my life just to Buddhism. I wanted to have a family and start a career. I always wanted those things.”

After 10 months in Thailand, Theanthong returned stateside and was employed in the technology sector during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s, but his inclination to help people never wavered. He applied to police departments across the nation—but not to the NYPD, he noted, because the starting salary was not competitive. His priorities changed on Sept. 11, 2001. During his morning commute over the George Washington Bridge, he stared at the acrid smoke billowing from Lower Manhattan. Theanthong could no longer ignore his call to service; and the calling was to serve his hometown.

By August 2003, Theanthong was running laps at the Police Academy and, soon after, walking the beat in PSA 7. Over the years, he would move back and forth between the Patrol Services Bureau and the Detective Bureau, almost entirely in the Bronx, while steadily advancing in rank. His assignments included supervising Anti-Crime and SNEU teams at the 42nd Precinct, the BRAM and the Precinct Detective Squad at the 47th Precinct, where he was retained as a lieutenant, and the Precinct Detective Squad at the 49th Precinct. Then came the Financial Crimes Task Force, before he headed to the Central Robbery Division as a captain. Recently, Theanthong was tapped to be commanding officer of the 49th Precinct.

Through all the promotions and moving around, there was always one constant: Theanthong’s passion for helping others, whether it be victims of crime or fellow cops.

“Being a cop is not so different from being a monk,” he said. “Patience, compassion, empathy, trying to live through another person’s eyes. We shouldn’t dismiss smaller issues, like loud noise or a blocked driveway. The people dealing with that are experiencing severe stress levels.”

With the increase in grand larcenies and grand larceny–autos in his new command, Theanthong understands that driving down index crimes is as important as understanding victims’ trauma.

“When someone has something physically taken from them or are injured, not only do they lose that property, but a piece of themselves as well,” he said. “They feel like they’ve been violated. Their frustration and sense of violation is so strong.”

At a recent press conference in City Hall, during which NYPD leadership discussed several high-profile incidents and reported that overall crime was down citywide, the secretary of the 49th Precinct Community Council, who was in attendance, remarked that what is true in the aggregate is not necessarily true in the individual case.

“Here’s the latest 49th Precinct crime stats, which show, for a two-year period, crime is up 34.89 percent and not one category is down,” the man pointed out. Chief of Crime Control Strategies Michael LiPetri responded that the 49th Precinct would be designated a summer zone this year and would see a significant number of cops posted at problematic locations. Then, remarkably, Chief of Department Jeffrey Maddrey added: “We brought back our old face, old squad commander, Captain Theanthong. We already see the difference. For the week, 28-days, he’s pushing crime down. He was the squad commander there. He knows the place well.”

The moment was reminiscent of a dugout manager motioning to the bullpen that it was time to bring in the team’s most reliable relief pitcher. When asked about the possible additional pressure of having to perform as a big-game “closer,” Theanthong laughed.

“If you panic, your guys are going to panic,” he said. “We’re all going to do this together.”

Addendum: With his recent change of assignment, Captain Theanthong became the first NYPD precinct commander of Thai descent.